Is the Public Still Persuadable? with Anand Giridharadas

S1E2: Anand Giridharadas and David Corn

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

If you’ve been up at night wondering how to save democracy and communicate effectively with people on the opposite side of the political spectrum, tune into MSNBC on-air political correspondent Anand Giridharadas in conversation with Washington DC Bureau Chief for Mother Jones David Corn for a powerful hopeful chat on the state of American and effective organizing.

Read the Trascript

[“We Got a Listen” bouncy and funky theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey all, what’s going on? You’re listening to Chicago Humanities Tapes, the audio arm of Chicago’s long-running festival creating experiences through culture, creativity, and connection. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, here to bring you the best of the best of the live festival from the past 30 years… and counting.

Today we’re going to hear from bestselling author and regular on the news circuit Anand Giridhiradas –

Mika Brzezinski: Author and MSNBC political correspondent Anand Giridharadas.

Joe Scarborough: His recent book is The Persuaders: At the Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy.

Trevor Noah: Welcome to the Daily Show/

Anand Giridharadas: Thank you.

– in conversation with political journalist David Corn on the concept of persuadability: how do you talk to someone on the opposite end of the political spectrum, especially with the goal of change in mind? The timing of this conversation from our 2022 season is great, with Giridharadas having just published his new book The Persuaders. And if you’re listening to this in real time, our 2023 Spring season is underway as we speak! You still have a chance to grab tickets to see some of your favorite speakers - make sure you don’t miss Stacey Abrams, Miranda July with Carrie Brownstein, physicist Michio Kaku (MIH-chee-oh KAH-koo), Ruth E. Carter who just won the Oscar for Best Costume Design for Black Panther: Wakanda Forever… Head over to chicagohumanities [dot] org for ticket information, to sign up for our email list to be the first to know about events, or become a member for exclusive events and insider perks.

Today, we’ll hear Giridharadas’s take on the political divide. An international best-selling author, his work is fearless, entertaining, and fiercely human, as he centers his storytelling on thoughtful interviews with real people. His previous books include reflections on his memories of immigrating from India to America, reporting on post-9/11 xenophobia and domestic terrorism, and challenging the upper crust and billionaires to do the day-to-day democratic work to truly change the world. I’m always struck by how hopeful his work is, replete with calls to action.

A former foreign correspondent and columnist for The New York Times for more than a decade, he has also written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Time.

He chats with David Corn - Washington DC’s Bureau Chief for Mother Jones. Corn’s been Washington's editor for The Nation and appeared regularly on FOX News, MSNBC, and NPR. His books bring his real rock n’ roll DC energy to topics such as the history of the Republican Party and Russia’s influence on the 2016 election.

They chat on: who is responsible for persuading the actual change and policy makers? How do you talk to someone whose opinions just, gut you to your core? Why are we all so fixated on AI at the moment? And stick around for a great Q&A at the end, with thoughtful questions from Gen Z.

This conversation was recorded around the Midterms in fall of 2022 - so you can feel the weight of uncertainty but progressive productivity in the air - at Northwestern University (go Wildcats).

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Hi Chicago. Great to see you. Hello.

DAVID CORN: Hello. Thanks for coming.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: It's a good looking crowd, David.

DAVID CORN: Yeah. You know, we have become tremendous Chicago fans in the last four, 24 hours. I would.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Say we lived a week in the last 24.

DAVID CORN: Hours. Yeah. So we can't.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: You go to Rosa's lounge. You really you really can live a week. A week and a night.

DAVID CORN: Yes. So we'll jump into it. How did the Republican party get to where it is today? Right? It it's a bit funny to me. I had a book that came out a couple of weeks ago and it's kind of a bookend to yours, it's called American Psychosis.

It is a history of how the Republican Party over the last 70 years has tried to exploit and encourage extremism. The point being that there's nothing new with what Trump is doing. It may be intensified and more extreme, but it's always been part of the the DNA of the Republican Party and the conversation it has tried to have with its own base and with the political culture at large. And in your book, you're looking at people mainly, you know, people on the left who are trying to figure out how to have honest conversations both with each other and with people who might not share their views. And to determine in this highly tribalized, divisive political environment that we live in now whether there is room for persuasion and change. You want to talk about this?

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Yeah. Well, first of all, thank you all for coming. It's an amazing thing, particularly in this moment and climate, when people still actually have questions and want to learn and come to a humanities festival, are interested in books, interested in ideas. That itself is a is an incredible thing in a time when those values are under threat and. So thank you for being here. I think the the motivation, the impetus for the book The Persuaders, is that in America politically it's not a contest between 31% and 39% marginal tax rates or this way of delivering health care to people, or that way of delivering health care to people. Or should we have an estate tax or not have an estate tax? It is now a contest between a pro-democracy side and an anti-democracy side. Right. I mean, I don't even think Republicans and Democrats are particularly useful frame anymore. There is a pro-democracy movement in this country and an anti democracy movement. And as I looked out on what was happening in the last few years. It seemed to me that with the help of with Russian encouragement, building on what we were doing to ourselves and each other. The pro-democracy movement, to be frank. Is simply not winning. And it's not just not winning. And here this is a provocative point, but I think it's true. The anti-democracy movement is doing a whole bunch of shenanigans and unfair play. There's no question. Right. Voter suppression. Gerrymandering. Some things that are just inbuilt in our system, like the Electoral College, which amplifies minority views the Senate, you know, Steve Bannon's army of state election fiddlers. All that's happening unfair play. Here's the provocative point. I don't think the pro-democracy movement is struggling to win simply because of the unfair play. I actually think it is struggling to win hearts and minds. I don't think it's winning the argument. If the fight was completely fair, I think we would still be losing the argument for the future. And one simple source of evidence for that is polling. There's no voter suppression in polling. Polling is just calling people on the phone and asking them what they think. And right now, we are calling people on the phone, thousands of people every day there's a new poll and asking them, do you want one movement that is committed to political violence as a legitimate tool of getting the world you want and overthrowing election free and fair election results? And about 46% of Americans on the phone are saying yes. I don't believe that that is false consciousness or that there's the polls are being rigged. I absolutely take very seriously that 46% of Americans absolutely want that world. And so it seems to me a pro-democracy movement that is only polling at 46% is an abject failure. And we need to understand what is it that has allowed a completely dystopian far right movement to command so much allegiance, to make people so excited, to make people so loyal for awful purposes? But hats off on building a real movement on that side where a lot of people are revved up to participate in their own destruction. You know, some incredible movement building. And on the pro-democracy side, there is a smugness about we're doing the right thing.

We stand for the right policies, so people should just get it. People are telling us they fear inflation. We should explain to them that's not as important as democracy. People are telling us they fear crime. We should tell them they're wrong if you actually do the right regressions. We don't need messaging because, you know, we know in our hearts we're helping people. I came to the very simple and devastating conclusion that we've gotten a lot better on the pro-democracy side at condemning fascism than out competing it, and that there's no plan to outcompete it. There's no plan to build a galvanizing, thrilling, openhearted, feisty, rooted, locally connected, even small evangelical movement to win souls, win hearts and minds and bury fascism in the garbage dump of history. And I decided I didn't have the answers to this in my own heart. So I set out to report and spent time with organizers, activists, cognitive scientists, a cult de-programmer, because that's where we are now. And others, but particularly organizers who are showing a new way for the pro-democracy side and we can get into some of the tactics and methods I learned from them. But the biggest thing I'll say about all the methods I learned from them. Is that the pro-democracy movement is barely even attempting most of the things that those organizers think will work and that is good news, because if we were leaving it all on the field and polling 46, 46, then the country would be over. But actually, the pro-democracy movement has not even turned on some of the engines that would be crucial to defeating this movement. And this book is a plea through the stories of people doing this work on the ground to to learn from them, to do what they're doing at the scale of the nation. And I deeply believe that if we do that, we can we can bury that movement and put it where it belongs.

[Audience applause.]

DAVID CORN: a majority of Americans believe democracy is at risk, not just a majority, an overwhelming majority. And then only 7% said it was an important priority for them. That's a pretty stunning drop off. And, you know, you call this you just referred to this multiple times as a pro-democracy movement. I certainly think that is an accurate description.

The people in your book. A lot of them are not working towards this abstract notion of protecting democracy. A lot of it is very granular. Let's get DACA into build back better. Let's defeat Proposition eight in California. And it's the left kind of going and doing a lot of different things that overlap. They do intersect, as the young ones say these days. And that's important. But it's, I think, a lot different than the other side, which is basically a big no. To a lot of things. So looking at all these various efforts that you report on, do you see them knitting themselves somehow into something grander and bigger that will have a bumper sticker?

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Yeah, it needs it. And I think when I talk about the pro-democracy movement, I'm not proposing that as the bumper sticker. Right. Like I'm. I'm having a meta conversation. About what? The many things they need to do. One of the really striking things I learned from these organizers and others that I studied is that. I think on the right, there is a a real understanding that a lot of what ends up in politics begins in the realm of emotion and psychology. Right? Like before people vote or even have a stance in their own head, they feel things. They feel in particular when talking talk about politics. They feel fear. They feel anxiety about all kinds to all of us. Right? Where they feel hope or they feel that generosity of spirit. They feel love. And there's a lot of our, the kind of, before you have a stance on the border. You see family separation and that does different things to different people. And I would argue my understanding of politics that ends up in stances or. You are experiencing change in your small town and you notice there's suddenly a lot more Spanish speaking people in your town. That's just an observation. It takes a lot of meaning making and processing to become this fear of immigrants.

The right is very good at understanding that the real work of politics is to take people from those stimuli to the stance that you want. So the right is not just asking you to chip in five bucks ten times a day and vote. The right is actually walking with its people all the time. Its media is fully oriented towards starting with the backing into the fears and anxieties you have. You could almost imagine the project of the right today as starting with an anthropological, astute, anthropological understanding of the fears and anxieties that are there. And then saying, How can I get you from there to the agenda that I want that's going to benefit kind of a handful of billionaires? And. When I look at the left, the pro-democracy side of the Democratic Party, call it whatever you want. I think there is instead a starting with like they're like vendors who are like I got these watches, right? And voters are like, I have a watch and they're like, Yeah, but I have watches.

DAVID CORN: It's a better watch.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: But have you seen these watches? Right. We start with like, I know you're afraid of crime in your neighborhood, but it may not matter if the planet ends. It's very like I call it Dem-splaining. Like, it's a kind of it's a kind of like, you think you're scared of this. But let me tell you, like, the data doesn't support what you are scared of or you shouldn't be scared of it, or like the thing you're scared of is bad. But like, a much bigger bad thing is going to happen to you. So please reprioritize your fear.

And I think a smarter movement would say I'm going to actually start with that same astute anthropological understanding of where people are, what's going on with them, the anxieties people have. And this has been and this is at the heart of the Persuaders book. This has been an era. We don't sometimes think about this. This has been an era the last 40, 50, 60 years of extraordinary change in every area of life. You know, I was a foreign correspondent in India right after college. And like it was like eight or 9% GDP growth, you know, similar to China, a little bit slower. And like the society was like being remade every four years. Right? Like, it just and I learned as a foreign correspondent, like the story was in India. And I think it's part of why India is now run by a fascist government. Like people's sense of themselves, like men and women's relations, families, like what work was how you treat your boss. Like all of it was like being erased every five years in this, like, very ancient culture that was suddenly growing so fast. And I. I cut my teeth as a reporter on that. And I came back here, and I realize that while we don't have eight or 9% GDP growth. In many ways, this era has kind of been like that here in ways that I don't think we acknowledge or is not so obviously told. Right.

Trading with China. That alone has changed every county in this country. It's changed the definition of masculinity in North Carolina and other places where people made stuff. Gone in three years. Suddenly. Sorry, you got to find a new definition of how you like, have esteem in your community. If you think about areas of real progress on gender, right, it's not a single household in America that hasn't obviously been upended by a massive empowerment of women playing all the roles women can and want to play. But no household is not changed by it. No man is unchanged by that need for a new self-understanding and a need to relate differently to women. Racial and gender progress. Demographic change. I could go on, you know these changes. And I basically think the right understands everything I just said, understands that it has left a lot of people kind of like.

Who am I in this new world? And it's not just bad people who feel that way. Right. I mean, which man in this country is not in some ways caught today between old ways of being a man that worked for your dad and grandfather, new ways of being a man that your son is very confidently figured out. And you're like. I don't want to be like my grandfather, but I can't quite so, so effortlessly be as woke as my son. Right. Which white person is not thinking about race. Conscious of race whether you're super woke or not woke is not going to train is not is not just thinking about whiteness as a concept which was really not a concept people talked about when I was growing up. Which white person is not confronting that and grappling with it in a way that their parents and grandparents were not? So on and so forth. And the right gets that this is going on, gets that we are roiled by these questions about ourselves

I think it's incumbent on those of us who want more democracy, more equality, more human rights to actually understand instead of hawking the watches in our in our jacket. To actually start with what is going on with people, start with a really empathetic view going on of people on our side, going on, people on the other side, going on to people in the middle. The reason I think we are losing groups that we should not be losing. Hispanic actually, men of color in general. There is a it's not this is not just a white supremacist movement. There is a real failure to start with people's anxiety, start with people's emotions in an era of churn and build a movement for good around that. And I think a lot of the organizers I write about in the book, they know how to do it. That's what they do in community. They don't start by hawking their wares. They start by building relationships based on who people are and what they're worried about. And I think it is possible for the pro-democracy movement to do this, to learn from it. But if you ever get DNC emails, you know it is not what they're doing now.

DAVID CORN: I'll take one issue with what you just said, that I don't think the Republicans have been astute. I think the exploitation of fear has been very easy for them to do and very obvious. I mean, my book starts with the McCarthy era and you think about the change that was going on there. To get to your point of change. There was an existential change that all of a sudden everyone realized their world could end in a moment, in a flash that you wouldn't even see. And there was great unease at the Cold War, the advent of nuclear terror. And first, a guy named Richard Nixon. Some people might remember him, but then Joe McCarthy came along, did it even better. And they raised fear about internal subversion. And the other side, the enemy, destroying your country as a way of explaining why you felt bad and uneasy and worried and scared. And it clicked. It worked really well. And then it worked well with the Southern Strategy. It worked worked well with Reagan and the rise of the religious right. When the Moral Majority came, that came came into being. And Reagan embraced them, even as members of the Moral Majority were saying that gay people could be executed under God's law. You know, it was like, look at the change. Gay people are getting rights. And time and time again, Republicans have just said, let's push the fear button. It's not a very difficult thing to do. You know, there is I think, you know, you mention psychology. There is, I think, somewhat of a psychology, a psychological difference. And there's actually academic research on this between liberals and conservatives and who respond more to motivations based on fear, motivations based on hope and how you process threats.

The people in your book get this and they know this and they're responding to this, they're trying to figure out how to work around it and come at this from different angles. And there's one person in particular I want to I want to raise, because this was to me, the most somewhat engaging and even inspiring chapter because it was very ended up being very practical and pragmatic. You should describe a little bit who she is, but really, she has been out there for years working on messaging for progressives that I think really, really applies not just to the groups doing these individual campaigns on issues, but to the overall Democratic Capital D. Project. And so I'm going to ask you also to describe to the audience, you know, her ideas about not red meat, but blue meat and and why brownies are good.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: This is a to be clear, we're kind of talking about the big ideas in the book, but this is not a big ideas book. This is a book about people and stories of people doing this work. Each chapter is about a story or a group of people or a person doing this. And one of the chapters toward the end is called The Art of Messaging, and it's about Anat Shenker-Osorio. So how many of you know Anat Shenker-Osorio's work, few people there. You know this is also just a very interesting thing about the left, Anat Shenker-Osorio is the most important message person on the left.

She's like all the movement spaces use are all the activist spaces she has shaped the conversations you all have heard. What presidential candidates say but would never be hired by this White House would never be hired by the DNC. Right. Even though everyone will tell you she is on the cutting edge of thinking of how Democrats can win against fascism in a time of racial division, etc. So I spent a lot of time with her over the past few of the last year of the Trump presidency and then the first year of Biden as she was doing some work, first trying to make sure that there was a, you know, transition of power if Trump lost and that it would actually be followed. She did a lot of behind the scenes work on how do you message that? And had very counterintuitive things to say there. Don't portray him as a strong man. It actually reinforces that, like persuade persuade people that he's a bumbling idiot who's going to cling on to power because he knows he can't win,

She does these kind of secret Zooms with like a thousand people who are all working on various phases of these, these things. And that's like the messaging guru. And so then when you are hearing some people say something on CNN or defend Build Back Better in this or those terms, it's often because someone like Anat just did a Zoom with a thousand activists and organizers telling them how to frame these issues, and Anat's project, as I understand it, she is running a kind of one woman insurgency against the Democratic Party's dominant approach to persuasion. This is not just use this phrase or that phrase. She is trying to turn the Democratic Party's approach to persuasion upside down. The existing reigning approach, I would call persuasion through dilution. Which is. Democrats will start with a kind of beautiful philosophical vision of a thing. Health care for all people. Or, you know, a humane immigration system or something like that. And then the idea is you persuade by adding a whole lot of water to that beautiful dream. And for any of you who are like home cooks here, you know that just adding a lot of water to something can sometimes make it, like, kind of disgusting. And and so now you end up with this very thin gruel of like an immigration system that is like sort of a little more humane, but like deports a lot of people or health care that is sort of for most people, but only through private insurance. And it may not cover a whole bunch of stuff you have. And these kind of Democratic policies that we all know well. And the approach to persuasion that that reflects is it's this obsession with the working white working class swing voter in like certain counties of Pennsylvania, Pennsyltucky it's called sometimes and where if we water it down, maybe those people who think we're communists will not think we're communists. And we hope these really loyal voters who have been with us forever will just come along no matter what. And what often happens to Democrats is those people still think you're communists, and now you've left your base who you owe a lot to. You left them cold and sad, and you frankly have not taken care of them in a way justified by their enthusiasm for you. They've had your back. You haven't had theirs. Anat is trying to turn this upside down. Anat's theory of persuasion, which has grown more and more allegiance in the in the party, except for at the very top, is you persuade not by diluting and having thin gruel. But by standing very firmly and bravely in some ambitious truths and aspirations and you actually dig your feet in, you become actually much more intransigent about a universal health care system or a humane immigration system. But then with the self-confidence of someone who is quite dug in, you reach out through rhetoric, through an empathetic understanding of the moral intuitions of other people and speaking to them more effectively. You persuade by convincing people that there's actually a Christian case for fighting climate change, something the Democrats should be doing in a 70 something percent Christian country that totally failed to do. You you make arguments for something like Medicare for All, which, by the way, should be renamed Freedom Care. If you look at any opinion polling on values in this country and should not be named after a government program, should be named after a value people hold, and then you should have all the rhetoric around something like Medicare for All about how it would be a new birth of freedom in this country, how it would free you from your terrible bosses and free you from your stupid job. And you could have a business idea you can go do it because you wouldn't lose your health care and your kids wouldn't be left high and dry just because you pursued a dream. Right. Like, there's so many ways to talk about so many things. And instead of doing this thing where you just cut your health care plan in half to appease people, maybe stick, stick to something bold and then explain it. And so then Anat's work is having dug in. How do you explain it? What are those ways to do it? And at the heart of her theory is don't neglect those people who had your back. Don't neglect that base. Those are your people. Make them so excited about what you're doing. Give them something to talk about, as Bonnie Raitt said, and then they will talk about it to everybody around them. And you know what? They have friends and they have neighbors and they have coworkers and they have cousins who are undecided.

These persuadable, moderate voters that everybody's chasing in Anat's analysis they are not people in the middle. They are people who are torn. They are contradicted, as Beyonce says on her new album. They are they can think in different moral frames. They don't yet have a baked worldview the way many of you probably have a baked worldview as people who come to a humanities festival. Right. They're like, it's really true. And this is maybe at the core of the book. Is that we have forgotten that a lot of voters can toggle into completely different moral frames without that much effort. Right. And we know this. Like, look at the progress on gay rights in this country. Right. Look at the progress on recognizing the humanity of trans people. We're not there yet. But like there's been a lot of motion. We need to give ourselves credit for the motion. Look at the conversations on race we're having, look at the reckonings around gender we're having like we move, we move. Like it's not true that nothing changes and people are capable of reaching other conclusions. And we need to build the kind of movement that gives people something to talk about. So they're talking to everybody they know and exciting people. And I think what Anat is doing is game changing if it can be listened to in the highest centers of power in this country.

DAVID CORN: What was most compelling in her case was this analysis. The people in the middle are not moderates, per se, that she called being a little situational, not ideological. And the framework that both sides have tended to work with over the years is, okay there are liberals here, there are conservatives there, people in the middle have to be a bit of both. And it's not that they're thinking in those terms. These are people full of contradictions and confusing ideas and they can be won, won over. When she talked about messaging, it was. And it kind of rang a bell. It was. Messaging has to tend to be on the on the Democratic liberal side, positive. So abolishing ICE. Ending climate change, destroying white supremacy. She doesn't take issue with any of that. But these are all about negative things, defeating something negative rather than a inclusive society, a healthy economy and environment. And we tend to come along and say there's a problem. It really sucks and you have to pay attention to this.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: And and you're not donating enough.

DAVID CORN: And that works with a very small number of people who are already with you. And if the left or the progressive movement and the Democratic Party can't figure out how to do these more expansive and inspiring messages. They're not going to get those people who are bobbing about on the sea.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: This is not just a messaging thing, right? Like saying you want a planet where we can all thrive versus saying end climate change is not just like a switching a sentence. Getting to positive demands actually requires further thinking, that I think is often not happened or not happening. Right. Like even health care. Even a positive demand like universal health care, it's still not pushing the thinking far enough. What does the world look like if we win? Right. Like there's this hospital ad in New York City that I've been seeing that's the great hospital ad. And the ad is "stay amazing." Like, that's actually like no one no one values health care as a thing in itself. Health care is just a tool to, like, stay amazing. Like, know your kids longer. Yeah. Right. So we don't.

DAVID CORN: Be able to chew your food, be able to hear your spouse, be able to see better.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Correct.

DAVID CORN: Right.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: And so it's a discipline to get past abolish ICE. Great policy. Right. But like, what do you. What do we want? What do we want? What's the world look like when we win? Anat's, another of her mantras: Paint the Beautiful tomorrow.

DAVID CORN: Yeah. Okay. So now we go to your questions

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: Hello. My name is Shayna. Thank you for this thrilling talk. My question is, in your research, what did you learn about a sense of urgency and time? Because I think particularly around the climate crisis, for a lot of us on the left, there is this sense of being in your head against the wall, because every day matters, every second matters. So what did you learn about how activists are successfully tackling this sense of time and urgency?

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: I love that question because the climate is obviously the most dramatic of all of these situations. A real reckoning. About how the environmental movement over the last many decades went down a rhetorical course that kind of felt like, downer and like, homework. Broccoli, like. Like you are bad. Like, why do you eat meat like you're bad? Like why? Why aren't you doing this? Why aren't you doing that? Like just haranguing, lecturing, like there's a a, you know, and look, it's a movement to to prevent the end of habitable life on Earth. So, like, forgive it for being dour. But there is I had this fascinating conversation, Varshini Prakash, who runs the Sunrise Movement and others about this, where I think the younger generation is saying. It was, in a way, a very privileged person's movement because it was people who themselves were fine in life and they could afford to like have this kind of great struggle and everything's terrible and dire. And for this, the conversation I'm hearing now that relates to the persuaders on climate is, hold on. What would it look like to have a climate movement that that dealt with that time challenge by being thrilling. By saying it's an awesome world we're going to build because of the prompt of a change in climate. Like we're going to have blimps. Bill McKibben wrote this great piece about this. Like, why aren't we telling anybody about the blimps? Like, we're going to have blimps and it's going to be so.

DAVID CORN: Not flying cars but blimps, but blimps.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: But blimps, we're going to get blimps and we have to get blimps to do cargo like if we want to fight this thing. But like, it's like, how come no one selling us the blimps? But everybody's saying you can't eat beef. Like, both are probably part of the future. The blimp thing's probably more real than, like, people never eating beef anymore. But, like, we know about the beef being taken away, but we don't know about the blimps. That's our. That's our failure. Right? How come we go to West Virginia or Louisiana, on oil West Virginia? You know, to tell these people that the way they're living is bad. They have black lung and we don't, but they're clinging to it. And I think that's on us, not on them. I don't think we have offered them a package of the future that feels more fun, more exciting. You know, we're going to be able to fix things on racial justice and the architecture of this country because of climate that we would never have fixed for any other reason, because there's going to be money and there already is that money to do a bunch of reparative stuff around transport, around housing, rent, all kinds of right. Like, why can't we tell a story about the kind of amazing racial progress that's going to happen because of climate? Like, there's this hallways that back up down the road. We went down. There's a whole other road we could have gone down of offering people a thrilling, galvanizing, all hands on deck project of making the kind of society we should always have been living in with the prompt of climate. And there's been a total failure to do that. And it's not only more effective, but it's a true story. And so I you know, and I'll leave you on this. I did an interview with Steve Bannon a few years ago for a I was writing a profile of Bernie Sanders for Time magazine. And I wanted to understand why people on the right thought of Bernie. And we got into a conversation actually about AOC with Steve Bannon. And Steve Bannon said to me. And I hope he's thinking of this in prison now. And. And I'm sure that's all he's thinking about.

I think he was sitting in front of a picture of a monkey drinking a Coke like a painting. And and he said to me, AOC is the only person on the left that I fear. And I said, why is she the only person on the left you fear? And he said, I said, Why? And he said, Because she understands. And he wasn't endorsing this view. But her understanding of the world is that climate is the thing that stands both kind of above and below all of the things and is the only thing that is so huge that at some point we'll have no choice but to face it. At some point, everyone will come around to like not wanting to die. Whereas everything else is just like an ongoing contest forever. Right. And he said she understands that climate will justify a whole of society mobilization to do a thousand different things and at once. And he actually compared it to World War Two. Basically, she she and she has used that analogy. He she understands that we'll be able to sell at some point a whole of society, war-like mobilization, to do everything right, to fix our transport, to redress racial justice, to do all the things that you actually have to do just to fight climate. And he says she understands, and once she's able to do that. There's nothing they won't be able to do. Right. And so I, I think about that a lot. And I hope he is as well in his little cell. You know, I wish I could share that optimism of Steve Bannon. I mean, that's the incredibly hopeful view.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Hi. My name is Elizabeth. I'm a 16 year old girl and I've been watching my country change and evolve over the years. But my question for you is, how can you tell when democracy is changing, especially when you're talking about the pro-democracy movement?

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: how can you protect your democracy and make sure it doesn't, like, slip into the hands of, like, our government?

DAVID CORN: Well, I think the riot was one strong indication on January six. But there are obviously a lot of deeper and more pervasive indicators as well.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: First of all, I mean, the signs like symptoms, right. It's become increasingly normal for people to run for office on the program of throwing out election results, which has all kinds of layers of irony. But that's not a that's not a fringe thing anymore. I think most Republicans running for Congress right now say the election was stolen in 2020, which it was not. I think another symptom would be mainstream people saying political violence is an acceptable tool for getting the kind of world you want that's now completely mainstream in one of the two main parties. And then I think there's another way to understand democracy dying, which is more of the whimper than the bang. Although we're focused on the bang January 6th, I think the whimper is like at some point we all get used to the idea that things most of us want will never happen. And like, maybe that's actually what the death of democracy is just like. Like, they're just a whole list of things you and I could make of things 80% of us want. That we all know will never happen and so is that a democracy? And the one bigger frame I would put on why it's dying that's incredibly important is I think we have to tell the hopeful story first that explains the revolt against democracy and what I would call the revolt against the future. The truth is, this country was founded a long time ago on some very lofty promises that it was not brave enough to live up to in full at the time for a whole bunch of people. And in the way that people get better, the country's gotten better. It's gotten truer to itself. It's become more self-aware. It has, you know, acquired more of that courage to be what it promised. And I think it's actually gotten closer. In the last few decades, then a lot of our ancestors would have imagined. We don't tell ourselves that story enough because we're so focused on right right rightfully and all the unfinished business. But we've gotten we've gotten to a place of kind of unimaginable levels of inclusion that like shame our ancestors for all the people living among us, that they did not see as human and they did not treat well. And I think when you start there, then you understand what these people are doing on the far right as a revolt against the future. They're not the protagonists of this story. We're not living in their world. They're living in our world. We have actually built an incredible kind of country. We are building an incredible kind of country. And no one on the left says this. No one the left is proud of this. We're building a country that is made of the world. Right, that looks like the world where people from every kind of background can come here can become American. It's imperfect. We haven't extended it to everybody. We've been flawed. But what we are doing, what we are attempting is awesome. It's literally awesome. It's an awesome goal. France isn't trying it. Germany is. Those are all white countries with gas populations. If you actually spend time there, you know. So, so America, "stay amazing." Stay amazing. America, stay, stay amazing. I think we have the bumper stickers. Yes.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: Gentlemen, thanks for your time. My name is Raj, so I work in the field of artificial intelligence. And in five years, it's going to be very disruptive in the world. So when you wrote the book in David, in your books to A.I. allows the ability, as it's being used today, to kind of reinforce these echo chambers. Right. And if you look at COVID, we become more isolated as a society where if you look at the sixties and seventies, even the eighties, you had neighborhood clubs. People go to the local tap and you'd have these discussions. But as we live more in our phones and we lack that face to face contact to have these conversations, how do we utilize technology to kind of bring us together as this pose has been used to divide us over the past ten years?

DAVID CORN: I think you should be the next speaker for a whole hour.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: I love your question, but I want to say, like, I don't think AI and I'm not the AI expert, but I would just say this about any tool. It is always humans who choose to use these things in good ways or bad ways. When I see Silicon Valley in particular, I see a bunch of like very limited, morally limited men who own these tools. And I like to me the AI we've gotten has to do with like Mark Zuckerberg's like a small, limited man. I'm I'm just serious. He's just like he's like he's not I don't even know. He's he's just limited like Elon Musk. He's just limited. Right. And so like the people who built YouTube, they're just limited. Like, I meet them socially. I know them like they're fine at like the thing they do. They're often like very little understanding of people. And so when you're in charge of like, how should people learn or things like that? And the people in charge of friendship, like have no friends that, you know, that kind of thing. And I think we need people to use these tools for good. Is there AI, I don't know the technical answer, but I would venture that there's A.I. that can make people find common ground and have better conversations with each other. And not only A.I. that can make people dunk on each other,

And you're right, David, there is this incredible thing called deep canvasing that is the antidote to those silos. And if, you know, if I've persuaded you today to to find things you can do, because we can't just wait for Joe Biden to start doing, you know, things that he's not doing, although he needs to do that. And I'm sure all of you want to find ways to do things right. Like, you know, excuse my language, but like, fuck despair. Like, I am so tired of despairing for the last seven years. Like, I'm ready for something else, and I trust many of you are ready for something else. So here's a thing you can go do. You can go look it up. You can go train yourself in a few hours online and then you can go do it. And it's called Deep Canvasing. And it is a remarkable experiment that grew out of the gay rights movement in California, where they realized their own friends and neighbors were voting against them on gay marriage. And they said, we want to go knock on their doors, not all gay people. And it's totally normal to absolutely not want to go knock on the doors of people who are against you. And that's probably most reasonable people's stance. But some minority of them wanted to go find out what's going on there. And thus began this experiment that was going to doors, knocking on the door, not giving a flier and leaving in 10 seconds, which is the canvasing, you know. Staying for 30, 40 minutes. And it has become this mass persuasion project that is happening in all 50 states in this country, led by organizations like People's Action and others. Where you go and you elicit from people, you listen. You strategically listen. Why do you feel that way about gay people? Why do you feel that way about immigrants? And then people say some obnoxious things sometimes and in in a way that even made me feel like complicit just standing there. You don't say you don't call it out at that moment. Oh, you got some bile coming out of you. Do you have any more bile? I would. I would be interested if there was more bile behind that bile. You got any more bile. I'm I. Yet? No, please. I have this whole bucket. Just please get like, more. Give me your bile. Right. And it's the opposite of Twitter culture is the opposite of what those algorithm. It's just like calling in instead of calling out.

They start to look for sources of dissonance within you with your own stance, not trying to implant some microchip of their conviction in you. Trying to say, okay, you feel that way about immigrants. You feel immigrants are lazy. You feel that trans people are a danger to your kids. Okay. Do you also feel other ways about like do you maybe you're a champion of underdogs and you really self-identify as someone who's always pulling for the underdog in a situation. You're a lifelong Mets fan. And and what these people have found may sound improbable, but they've done it. And it's been the subject of peer reviewed studies. They have found that playing up that identity of I'm a champion of underdogs and getting people to realize, well, what you're saying on immigration is not consistent with your view, that you stand up for people knocked down and counted out, or what you're saying about trans people doesn't square or or violates the fact that when you moved to L.A. as a real example, I saw in a beautiful canvasing video when you moved to L.A., you were treated like crap by your coworkers because you didn't belong in L.A. and that was the hardest moment of your life that you remember. How does that square with how you've been treating your trans niece and you see this woman go, Oh. Oh, shit. What have I done to my niece? And if I leave you with one thought, it's that in an age of polarization, we have been lulled with some, Russian help, into thinking that the other side is simple, monolithic, only has one story about them. We know we're complicated. We know we're like a roiling contest of feelings all the time. You have what you think about immigration or you have, but you also think other things you have b-sides what everybody has, b-sides or a lot of people have b-sides and the work. And I am so grateful that we're living in a time where there are these organizers, these persuaders around the country who are refusing the great write off that so many of us have participated. Those people will never change. They'll never. They voted for this. They voted for that. Let them be. There's a group of us, a group among us who is pursuing the idea that people have a second story in them, that people have these sources of dissonance. And if you strategically empathetically, always pragmatically, if these people are trying to win, they're not trying to have beautiful conversations. But if you approach in that spirit, you can move minds. They are doing it. They show it's possible. And I think it's just one example of what is at the heart of this book, which is that if you believe people can change, you still believe in democracy. If you believe people cannot change, you are actually asking to be ruled by force and by tyranny. And I think it is as dark as this moment feels. It is incredibly possible, plausible for us to wrest back the kind of mantle of progress and change, celebrate the accomplishments of the pro-democracy, pro-human rights side, tell the better story about America, build a more exciting movement, command attention, galvanize people and win. And I think we will. And I hope you all find ways to become better persuaders in your own in your own life and communities as well.

DAVID CORN: Oh, I know. But I know a lot of you out there are always looking for hope in these times. You just got a good heaping portion of it. You can get more. He has a newsletter. Tell people how they can sign up for yours.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: It's called mine is called The.Ink. We have any The.Ink subscribers here? Yes. Yes. Thank you for being here. Everyone else is. I like you being here also. So you can go to The.Ink very simple website and it's, you know, free newsletter with all kinds of interviews and discussions of this of this subject.

DAVID CORN: And mine is called is called Our Land and you can get that if you go to davidcorn.com. So thank you all for coming. Thank you. To the Chicago Humanities Festival, one of my favorite festivals and thank you to Chicago.

ANAND GIRIDHARADAS: Thank you so much.

[Audience applause]

[“We Got a Listen” theme music plays]

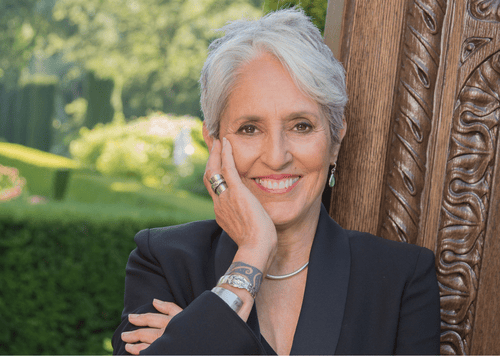

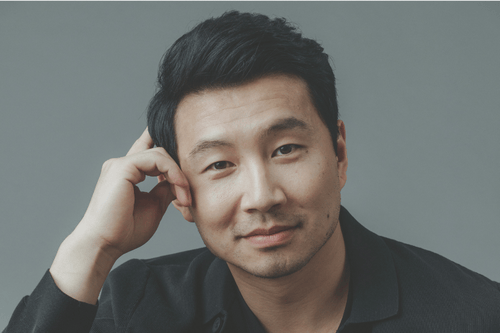

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Anand Giridharadas with David Corn live at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2022 at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Make sure to check out the show notes for links to Giridharadas and Corn’s newsletters and a full transcript for accessibility at chicagohumanities.org. We’ll be back in two weeks with one of our most exciting and popular events ever - my friends, it’s actor and Marvel superhero Simu Liu at the Music Box Theatre. Chatting with Joanne Molinaro, the audience can barely keep it together as he laughs through stories of being an Abercrombie model, shares inspirational tips to keep going in your pursuit as an actor, and a thoughtful perspective on a difficult early family dynamic. It really is a marvel… I’ll see myself out.

For more than 30 years, Chicago Humanities has created experiences through culture, creativity, and connection. Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with tons of support from the wonderful folks at Chicago Humanities who are booking these speakers for you and making them sound fantastic. Be sure to rate, share, and subscribe, available wherever you stream your podcasts and direct from our website. Thanks for listening, and as always, stay human!

SHOW NOTES

Watch the full conversation here.

CW: Strong language, in the name of democracy.

Anand Giridharadas ( L ) and David Corn ( R )

Anand Giridharadas, The Persuaders: At the Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy

Newsletter The.Ink

David Corn, American Psychosis: A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy

Newsletter Our Land

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- March 5, 2024

Rachel Maddow on History, Now, and What’s Next

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

- Podcast

- May 2, 2023

Marvel's Simu Liu on Acting, Abercrombie, and Family

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!