Adam Gopnik Delights in Investigating a New Skill

S3E14: Adam Gopnik

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Beloved New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik explores and celebrates his love of taking up new skills in midlife including magic, drawing, boxing, and even ballroom dancing with his adult daughter. Slipping in and out of French, he discusses his recent book Real Work: On the Mystery of Mastery with Gloria Groom, the chair of Painting and Sculpture of Europe and David and Mary Winton Green Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Read the Transcript

ADAM GOPNIK: I decided on an impulse to learn how to draw. Now, have you ever studied drawing?

GLORIA GROOM: No, I was cringing reading that chapter, because I have spent decades talking about art and I cannot draw.

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette tape player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey all, thanks for tuning into Chicago Humanities Tapes. We’re the audio extension of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I’m your host Alisa Rosenthal, and thanks for joining me on this journey of trying to find the answers to humanity’s biggest questions; luckily, we’ve got experts in pretty much every field, and can bring you the best and brightest minds from our live programs direct to your podcast queue.

Today, beloved New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik explores and celebrates his love of taking up new skills in midlife including magic, drawing, boxing, and even ballroom dancing with his adult daughter. He discusses his recent book Real Work: On the Mystery of Mastery with Gloria Groom, the chair of Painting and Sculpture of Europe and David and Mary Winton Green Curator at the Art Institute of Chicago.

With three decades of New Yorker contributions, ranging from fiction to memoir to critical essays to humor, Gopnik is a true champion of the humanities, delighting in writing about a variety of disciplines and also learning and inevitably mastering them.

He shows that the humanities are more than a class you had to take in high school – they’re a vital contribution to making life happy, healthy, and full. To check out some of Chicago Humanities’ upcoming live events, where you too can experience this artistic and thoughtful variety, head to chicagohumanities.org. We have tickets that just went on sale for Fall 2024, including acclaimed author Jesmyn Ward, chef Abra Berens with Greta Johnson, poet aja monet, and artist and author Anna Marie Tendler all live in Chicago.

This is Adam Gopnik with Gloria Groom, recorded live at the stunning sanctuary at Chicago’s Epiphany Center for the Arts sanctuary in May 2023.

ADAM GOPNIK: Good afternoon. Good afternoon to all of you. Wow. Oh my God.

GLORIA GROOM: Yeah.

ADAM GOPNIK: So to speak. Oh, yeah. I mean, are we worthy?

GLORIA GROOM: I'm not quite sure how to describe this place we're in right now.

ADAM GOPNIK: It's. It's astonishing. I was explaining to Gloria before we, before we started that, I've been on a, endless book tour. I am truly the Willy Loman of American letters. I go from one place to another with my little satchel of books, and the only places grand exists that I have been is the Bob Dylan Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Gloria's hometown.

GLORIA GROOM: That's great. Well, thank you all for coming. This is amazing. I am so happy to be back with Adam. Last time we were on a screen during Covid, so it was really great to see him in person today. And I have to just say, I love this book. I love the feeling of it. I just love it. The only, thing I would say is that I wish there were illustrations. You know?

ADAM GOPNIK: You're a visual person.

GLORIA GROOM: I kind of needed illustrations for all of these different masteries you took on, but what? Just to get started, though, it's dedicated to Kirk Varnedo, and I just wanted Adam to say something about this and how it relates to the book.

ADAM GOPNIK: Oh, thank you. Gloria, I'm I'm I'm glad to be glad you asked that. So Gloria and I should explain our celebrating our fourth decade of friendship. We met in 1985 at a, Art Institute symposium on La Grande Jatte, shot when I was a young pup, art historian. And she was a young pup curator and we pupped together, in doing this. But my the reason I was a young pup art historian and not yet full time, a full time writer, which is what I should have been, was because of Kirk Varnedo and Kirk. Kirk was, to my mind, the one of the great art historians of his generation and without question, the greatest teacher I've ever known or experienced. I, he was my professor in graduate school. We went on to curate a show together at the Museum of Modern Art, which traveled to Chicago called High and Low Modern Art and Popular Culture, a show which was notorious in its day and nostalgic in its aftermath, as tends to happen to highly controversial things. People, now remember it fondly, who hated it when it opened. Kirk was the greatest teacher I've ever known. I wrote a long essay about him in an earlier book of mine called Through the Children's Gate, because in a way that recalls Hemingway's beautiful lines in it's still I still get verklempt about it in Farewell to Arms, about how the world punishes those who are too gifted in, and beautiful. Kirk died very young of cancer. And, but before he did, in the last year of his life, he gave a brilliant set of lectures on the history of abstract art at the at the National Gallery in Washington. And simultaneously, though he knew it was he that he did not have long to live, he coached my son Luke's eight-year-old football team, called the Giant Metrozoids.

GLORIA GROOM: Oh I didn't know that.

ADAM GOPNIK: To victory. And in the story, which is called The Last of the Metrozoids, is about the intertwining of Kirk teaching, the most abstruse and difficult of subjects history of abstract art while coaching these eight year old boys and how you play football correctly. So it was a study and teaching, and what was so impressive was that the two activities were completely continuous and entangled. Everything that that he did as a as a most inspired lecturer I had ever heard, ever will here in our history. And everything he did as a as a football coach were overlap basically meaning that and this is thematic in this book, and it's why I dedicated it to Kirk, because he taught me this. It was always all about breaking it down into its smallest parts. Whatever the task you had, if you were going to play football, the crucial thing you spent two hours doing was learning how to get in the three point stance. You didn't run a play. You didn't do anything else. You just learned the right way of getting in the three point stance. And if you were going to study abstract art, what you did is you did not worry about the vast abstract and metaphysical generalizations about God knows what, the loss of the picture plane or the acquisition of the picture plane and commodity culture. You talked about what exactly Mondrian had been doing step by step, day by day, week by week, in his ascent, and then did the same with Frank Stella and that habit of breaking everything down and then building it back up from the smallest parts into the larger practices that could be cultural, artistic or recreational. And football was what he believed in profoundly. And. To such a degree. And I'm answering this question I know at greater length, but I can't resist this anecdote. We used to have a joke together because I'm a crazy football fan too, and we are both of us have wives who are not football fans, and we miss the greatest college game of all time - Boston College, Miami, 1983 - because we were off at a Shaker fair with our spouses, and it was a standing joke between us about something you wanted to do, but you couldn't do because your wife wanted to do something else. We would just say Boston College, Miami, and the last weekend of his life, we finally got to watch on tape Boston College versus Miami. And Kirk analyzed the famous winning pass that Doug Flutie threw with such acuity and brilliance and broke it down into its into its fundamental features. And it. And then. It passed away.

GLORIA GROOM: Wow.

ADAM GOPNIK: As you can see, it's a subject of deep emotion for me. So we should move on to something.

GLORIA GROOM: We'll move on.

ADAM GOPNIK: Something else. But just to say what great teachers give us. Right? There are two things. And I, to generalize. And it's a truth, because this book is very much about my falling in love with a series of teachers, because I love great teachers, and great teachers are irascible people, male and female. They're just difficult people. But the thing that they all have in common, in my experience, and every one of the teachers who I studied drawing and boxing and dancing and driving with, and in the course of assembling this book, all have in common is they set an incredibly high standard and don't compromise on the standard. But if you're prepared to pursue that standard with passion and perseverance, they have infinite patience for you. They'll they'll stick with you as you stumble in the belief that you can eventually dance. And that is what I think all great teachers have in common. And Kirk exemplified that well.

GLORIA GROOM: Wow. Thank you. One of the things, I just loved about, there's so many. I mean, it's you said it wasn't a self-help book, but it really is, because there's so much you can take away from it. And it's just, like, constant, witty but profound things that I was kept underlining, which is, you know, really not a good way to read a book, but I'm making all these little remarks. But I was thinking about it's the most to me. And I sort of followed your career. It's the most personal. Even Paris to the Moon, which was very personal about your five years. And you had a you had Olivia there. But when I thought about that, those challenges were imposed on you. I mean, you were there. Did you speak French before you went?

ADAM GOPNIK: Mehh kind of.

GLORIA GROOM: Okay, well, somehow you managed to deal in, you know, with the French and, the Parisian French, and it was. But those were like, imposed every day was a challenge. Everything you had to do just to survive was kind of like there. But this is a book about things that you chose to challenge yourself with. And I just and I was trying to think of the, the difference between a George Plimpton who would do, you know, he's going to do the football, he's going to do the timpani, he's going to do all that, these participatory journalistic things. But your book, it's more personal because everything you chose was for personal reasons. It's a connection to your family and your dearest friends.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes. This is this is true. You know, it's funny you mentioned Plimpton and you're the only person who has because obviously that was in the back of my mind. Plimpton, by the way, I don't know if people still remember George Plimpton, but he was the editor of the Paris Review, and he wrote a wonderful book called Paper Lion about, spending a summer in training camp with the Detroit Lions as a quarterback and so on. And, Plimpton was a wonderful writer, and I reference him on page five of the, you know, you do just to wave at his ghost, you know, coming, coming, coming round. But you're absolutely right. It's a totally different kind of enterprise. I first of all, I didn't have the idea of doing a book about learning to do things. I started learning to do things, and I realized it could become a book so that the, the, the two crucial the first two chapters, the chapter called The Real Work About Magic, happened because ]my son Luke fell in love with, card magic and got sort of precocious at it, had a fantastic, irascible teacher named Jamy Ian Swiss. And Jamy said to him, he was 13 at the time, hey, kid, you got to go out to Las Vegas if you're ever going to really learn magic. And his school in New York said, no, you don't have to go out to Las Vegas. And I said, you know what? Let's go to Las Vegas. And if you have never followed your 13 year old son to Las Vegas in order to dine with magicians, you haven't lived. And that happened, right? And I got fascinated by the the craft of magicians, because magicians for me are model art form, because unlike the painters and artists we work with and love, nobody takes them quite seriously, right? No one's going to write them up. In the art world, in The New Yorker, that's not the magic world. So and yet they have this incredibly high standard of craft. So I got fascinated by them. And then I, I had to learn. I decided on an impulse to learn how to draw. Now, have you ever studied drawing? Did you ever do.

GLORIA GROOM: No I was cringing reading that chapter, because I have spent decades talking about art and I cannot draw. And it.

ADAM GOPNIK: Well, it's. It's it's an endemic, what the French call diffamation professionnelle, a professional defamation of art critics and art historians. And let me add right away, my little brother, who's an art critic of note in and an art biography, wrote a great biography of Andy Warhol, was very offended by the whole thing because his feeling is is. Of course,]you don't have to draw well to talk well about art. And that's true. In the same way, you can be a great sports writer without being able to hit a fastball, or throw a punch. But I still persist in thinking, and at least this was my experience, that you don't have to be able to hit 100 mile per hour fastball to be a sportswriter. But if you've never stood there when 100 mile per hour fastball comes by at some deep level, you don't understand the level of skill and accomplishment that's necessary to play baseball. And I feel that having spent two years studying life drawing and never getting any, you know, never advancing in any significant way, but getting a little bit better over those two years, studying with another irascible teacher, a wonderful representational painter named Jacob Collins, who thinks that all art to our shame, Gloria, took a fundamentally wrong turn in 1855. And.

GLORIA GROOM: So pre Bouguereau.?

ADAM GOPNIK: Pre Bouguereau, pre Bouguereau just it's it's all you know it's Ingres and his students were the last real painters and everybody since has been going down. And all the people we love, Van Gogh, are just incompetent.

GLORIA GROOM: So color. In other words.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes color.

GLORIA GROOM: Is out.

ADAM GOPNIK: Anything. Only classical drawing counts. And he managed

to create a world for himself in New York, where when you walk into his ateliers, you might as well be in Paris in 1854, because it's nothing but plaster casts and nude models and natural light. And that's what you learn. And I you know, I don't share his tastes, but I respect the intensity of his conviction and of his commitment to a particular dream, which, parenthetically, is sort of avant garde because nobody else is doing it. But what I learned in and this is the one thing I took away from it is, is that art is made up of its minutia. It's made up of that thousand just, you know, when I was talking about Kirk and breaking things down into steps, football begins with a three point stance, and art begins with deciding that the the, the weight of your figure falls on the left rather than on the right. And when once you know how hard that is to register, you never look past it again. You know the and you never again make the leap to the metaphysical generalization too quickly. You know which we're inclined to do, and nobody more guilty of that than me. We're inclined to treat art as though artists are a series of pawns in a game of historical chess that we are playing against each other. And that's, truly a diffamation professionnelle of of our story.

GLORIA GROOM: I was fascinated by that chapter because. And I almost wanted to bring a sketchpad so you could demonstrate how you were taught. But the idea that you're not taught to draw what you see, like those, those projection things we used to get on the back of comics. Yes, yes, yes, you do that and that instead you had to think about a nation or a or a, you know, it was such a.

ADAM GOPNIK: Well, you know.

GLORIA GROOM: Strange technique.

ADAM GOPNIK: Out on the road, I would when I had a crowd. And thank you a little smaller than this one. I would begin by passing out drawing paper to everybody in the audience. I mean, I and I say the audience often was 5 or 10 people, that's that's life on the road. But and say to them, draw a, just draw the face of the person you're sitting next to, because inevitably everybody draws a kind of schematic version. Is that the face of the person sitting next to. And what Jacob taught me was you got to break your symbols set. Is he called, in other words, the conventional stereotypes with which we see the world, so that we see, you know, we make eyes and circles and noses as triangles and, and and mouses, bananas and so on. And he'd say, the way you break your symbal set isn't by observing, because that's too. What does that even mean? Said it's you have to form a new symbal set, he said. So look at someone's face and superimpose a watch face over it and then just ask yourself, is his eyebrow, is the person who draws his eyebrow at ten minutes past one? Or twelve minutes past one? Or or is the the formation of his forehead at three minutes before midnight or two minutes before midnight. And I spent weeks just making. He had a beautiful term for this tilts in time. And he would say to me, just like the three point stance, say, just make tilts in time. And I would make tilts in time and you become your eye, then becomes, newly acclimatized to the exactly the minutia of of us, of observation. And you start making faces instead of making faces, you know, and you start drawing faces instead of making faces. And it was it was a series of very counterintuitive little subroutines that Jacob had me learn exactly to break all the schematic information I have. We all have in our heads. Me particularly, perhaps, about and it was fascinating. And the great thing, Gloria, is. Is that even someone is utterly ungifted as I am, gets better. I mean, you never get good, but you get better.

GLORIA GROOM: And that that's another thing that struck me, is that there was a point when you were satisfied that you said, I mean, I don't think you you did two years, but you didn't go on. You you did the boxing with Joey. Yes. But you didn't want to be with an opponent. You didn't want to. And talk about that a little bit.

ADAM GOPNIK: Boxing of all the things that that I and as I said, it wasn't a conceptual, you know, conceptual idea or I'll learn all these things, just one thing after another, as happens to us in life and particularly, I think, in, shall we call it midlife? There are there are things that you want to do. One of the things I wanted to do was to it was also the pandemic impelled this a bit because you couldn't go to a gym, right? Because the gyms were all closed in New York, believe it or not. And, so I ended up taking boxing lessons within another amazing teacher, Joey Contrada. And if that's not a name from Central Casting, right, you say, what's the boxing teaching going to be called Joey let's call him Joe Joey Contrada. He said eh it's a little too on the nose, right? But that's what my boxing teacher is named. He's a great Muay Thai champion. What we ignorant ones call kickboxing. And Joey is a great teacher. And in the same way right what what I learned from Joey is that boxing you don't learn to box by unleashing your belligerence, right? You start, you know, throwing punches. You learn a very tightly choreographed sequence of blows: jab, jab, cross, slip, uppercut. Right. And it's typical one, and you have to just continually repeat them until it begins to seep into your insides, so you're no longer remembering it. You're just doing it as a seemingly seamless sequence and which is what you do. You persevere until that begins to happen. And the other thing which is fascinating is that the only way you can learn to box is I'm sure anyone knows who's done it is by imagining your opponent. There is no opponent, right? And but you have to constantly be thinking that every punch you throw is in anticipation of the punch he might throw, right? Otherwise, there's no structure to the art of boxing. There's no meaning to it exactly because you're not. Because you're not responding to anything. Now, I have never actually gotten in the ring with anyone. If you can find another five foot five, Jewish intellectual in his mid-sixties who has a lot of belligerence to unleash, preferably someone on the far right wing so I would have motivation. I will step in the ring and and we can fight a benefit. But until that moment arrives, it's all, you know, I'm doing it in, in, in a gym, but it's the most intellectually invigorating thing I've ever done because it, it exemplifies that process of breaking things down into the smaller parts and then building them back up, not not building them back up they become on their own. They become on their own a sequence because of the nature of, of, of our psychology, which is very good at implanting things until we get to do. I mean, dancing is the is the is the ultimate and the obvious statement of that. You stumble and then you step, and then you find your dancing and the dancing as, as you know, I was I did again, not in order to learn to dance. Though I always wanted to because my daughter Olivia, who as you say correctly, was the big event, the ll of Paris to the Moon. That book is about moving towards Olivia, my baby being born, our baby being born in Paris. And, Olivia now is in her early 20s. She went off to university and she, as I like to say, she came into herself rather than coming out to her parents. She discovered in university that she was queer, which is the word she prefers to gay, and delightfully so with a fantastic girlfriend. And we were not at all, troubled, much less shocked by it. But it was marked a new moment in our relationship. We'd always been extremely close. We're very similar in temperament and and tension, body tension. And I said to her when, when she was talking to me about it, instead of saying, darling, let's talk about, you know, intimate details of our life and yours, I said, baby, would you like to learn to do, ballroom dancing together? And to my surprise and delight, said, yes Dad I would love that. And we both knew it was a way of having an intimate conversation that wasn't verbal. And we're both very verbal people and this gave us a chance to have intimacy without discourse of that kind. And we started taking, dance lessons exactly again at the height of the pandemic. So we couldn't go in a dance studio and we would dance on the Esplanade in Central Park together. We had another wonderful teacher, Steve Dane, whose name we didn't know until afterwards because I. When he first introduced, we thought it was Steve Dance, which made a lot of sense. So we always called him Steve Dance.

GLORIA GROOM: Like Joey.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes, exactly.

GLORIA GROOM: From Central Casting.

ADAM GOPNIK: And we learned the foxtrot and the waltz, and we would go out there on Central Park and Steve would play, you know, old Sinatra records, Fly Me to the Moon.

GLORIA GROOM: Of course.

ADAM GOPNIK: And you'd and and Olivia and I would dance. And it was the most intimate conversation we ever had. And what was fascinating, too, Gloria, is it was very much, though non-verbal. It was about the material of her identity. Because she would tease me. She'd say, Dad, this is the most gendered activity we've ever done, because the man leads and the woman follows in, in ballroom dancing. And I said to her, I will whisper to it, you want to do it the other way round? Because Steve, good classical teacher, would say, Adam, now you step forward with your left foot. I say, do you want to do it the other way around and say, no, no. And I knew what she was saying was here in Central Park on the Esplanade, listening to Sinatra, we can make a little parenthesis in time where we're living in a in a pervious thing. I don't we don't need to subvert the foxtrot. The foxtrot is sufficiently subverted in in the world. And it became a very intimate conversation the two of us had. And that's the other theme of the book, is exactly that in everything we do involves everything we are, right. We can't do. It's what we. It's why we love art. I think it's because there's you can't make a gesture on canvas and a real artist can't. That doesn't evoke the entirety of the social world that she's in, or the entirety of the psychological state. You know, I think of sometimes of Elizabeth Murray, you know, the wonderful American painter who is, again, has left us sadly, too soon. But, you know, it was always fascinating to talk to her because she would do these wonderful pictures of, of kind of big cartoon feet and shoes. And I asked her once about them and I said, you know, why do you love that icon? She said, oh, those are my father's feet. Those are my father's shoes. He was he was an insurance salesman. And I you would come home at night and there'd be a big hole in his foot because he'd be pounding the pavement, and nobody had ever made that association. We talked about her love of cartoon or mastery of shape. But everything we do involves everything we are. And that's another. That's another lesson, I hope, with the book.

GLORIA GROOM: Wow. Well, I have so many questions. So one question, because Adam was an amazing art critic, as you know, for The New Yorker. Amazing because you knew artists, you knew living artists, but you also knew art history. And to me that you mastered that. You you nailed it, and yet you moved on. And why was that?

ADAM GOPNIK: Oh, it's a great question. For that very partly for that very reason. I mean, I hardly think I'd master.

GLORIA GROOM: Like the Jane. No, you were the John Russell, right? You could have, you were the John Russell.

ADAM GOPNIK: I did feel, I will give you a very straight answer to that, which I don't think I've ever said in public. I was going to see shortly after my son Luke was born, 1994, and I was the art critic of the The New Yorker, which was a wonderful job that I was blessedly lucky to have. And then and when we're young, we don't understand our blessings adequately, of such things. And I was going to a Bruce Nauman show of his clown torture videos, and I'm a big Nauman fan. I've written about Nauman. And I could explicate it, I could explain it, I could I could articulate it. He's an immensely serious and significant artist and all that. But as I was going through it, I thought to myself, I love this stuff, but I don't love it exclusively. I'm fascinated by how kids grow up. I'm fascinated by childhood, by France, by a million other things, and I'm not writing adequately about the things that I love. And finally, when you don't write as if you're a real writer as I hope I am, if you're not writing about the things.

GLORIA GROOM: I think we can say.

ADAM GOPNIK: No, I mean, you know, if you're, you know, the difference being that journalists, right from the outside in and writers right from the inside out. And if you're not writing adequately from your true insides, if you're faking your insides, it will become apparent to your readers that you that it's an abstract, again, activity. And I said at that moment said, I'm going to stop doing this not because I didn't love it, but because I loved other things equally, if not more. And I wanted to be writing about my actual inner life, not about my, my a secondary inner life. So I walked back to the office and I said to Tina Brown, who was then the editor, you know, I think I'd like to go somewhere and write from abroad and bless her. She said, well, London, of course. And I said, no, actually, I was thinking Paris. Paris, all right. And, and that basically and we, we and we and we turned it around and I it was I miss it sometimes because as you know better than I do, there are certain moments when you're with works of art that give you a charge so powerful that it is almost unbearable, right, that you can. We were just talking before I went to Saint-Rémy, the asylum where Van Gogh was sent after his Christmas episode in 1888 and painted his great, I think, his greatest pictures, just this past fall. And I was literally overwhelmed with emotion at being in that space and thinking about him, and I wanted to write something about it. And I will tell you that after how many years away, I signed a contract in 1990 to write a book on American art, A New History of American Art, and I am now going to do it. I'm now going to.

GLORIA GROOM: Oh good.

ADAM GOPNIK: Put it together. And with specially and with the and with help from the Art Institute, too, because the Art Institute very generously has put their whole, collection right is on is what's the word on the open source or right, which is fantastic.

GLORIA GROOM: Common something.

ADAM GOPNIK: Right so it's only, anyway, that's a very long winded answer to your question, but that's, that's the that's the reason. So, there are moments when I regret it only in as much as there's either a wonderful show that you want to praise or a terrible show that you want to assault. And, you know, the other thing I'd add is that I knew one great art critic intimately, Bob Hughes. Robert Hughes. Right. And I never felt that Bob was sufficiently fulfilled by being an art critic. He was a man of immense encyclopedic appetites, and he wrote about those later. He wrote good books about cities, but in a funny way, he had become professionalized as an art critic in a way that constrained the totality of his gift as a writer. And I never wanted to be in that position.

GLORIA GROOM: Interesting. And that brings me to something else, because as I was thinking about these different challenges and how you write so beautifully about how life is, you know, you go through school and our DNA is to avoid we try to escape what we aren't good at, what we think we won't be good at because we want to excel because that's the way we're programed. But I was also thinking about the idea of a recital, because I think that's what ruins things when you have to actually the culmination you're learning was for yourself. You were satisfied at this level. You, you, you'd been with the masters, you knew what you took. And I wonder if that's something. How do you feel about that? Because it seems like unless you had that final performance, that recital, whatever, you didn't study it.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yeah. Well, you know. In the book I make a distinction between. Oh, and I should tell quickly just that when I, I thought when I gave up art criticism as a full time thing, I thought Kirk Varneado, we were talking about, would be upset because his whole life was devoted to it. And I'd been very much his, his student, as in doing it.

GLORIA GROOM: After rugby.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes, exactly. And I went to tell him, I said, hey, I've decided I'm going to stop writing art criticism and go to France. And he said, oh, thank God. And I thought, huh? But he meant it in the most generous way. Man, I'm glad you're you've thrown your cap over the wall and you're you're following your heart. The the truth is, I make a distinction in the book, right, between achievement and accomplishment, which I know can seem a little subtle to people, but it's exactly, that's what I'm talking about. There's some things in life and we drive our kids in this society, particularly, towards achievement, which always involves the test, the recital, getting into the next school, flourishing in the next grade, all of those things that have tests at the end. And those are achievements. And we live in an achievement oriented society. And that's and we count the achievements by money, sometimes by grades, other times. But we are driven by achievement. And there's something empty about it. I mean, we all have to live in a real world of professional accomplish, of professional achievement, and we can't deny it. And I am as driven to those things as anyone and as guilty of that as anyone can be. But when I, my own kids were growing up, the thing that I couldn't help but notice is that what really gave them, meaning in their lives were the accomplishments they pursued on their own, whether it was learning card tricks or guitar chords or and sewing, that those, those, those accomplishments gave them a, a serene foundation of possibility that no number of scholastic or academic achievements ever could. And the the more that we encourage our kids and ourselves to pursue those accomplishments, which are self-generated, have a very high standard of craft. But in your sense, no recital at the end necessarily. The not only the happier will they be, but the better suited, the better fitted they'll be to find something in the world of achievement that they really want to achieve and get out of the terrible rat maze that we put kids in so often, right where the question is, if you keep studying, you can get the little sugar hit of sugar water and then turn to your right and there's another hit of sugar water awaiting you. And what where the center of the maze is much less the exit is is is never defined. So I think there's a huge value. And let me add and you know, this is something that you learn on on by listening. I'm not doing much of it today. I'm aware. But on the road you do. And one of the things that I was struck by and I hadn't fully internalized when I was writing the book, is that for so many people who are in middle age or early middle age or late middle age, you know, we tend to patronize people who are older and pursuing new things, right? We say, oh, good for you. You're doing macramé or doing yoga or whatever it is. And that's what this book is about in large part. But the truth is, and this is the good news that I bring, the gospel I bring is that those things, the, you know, the the older folks who are doing something new, they've got rocket fuel in their hands. That's not trivial or secondary. That's incredibly powerful. Because the single thing that we as human beings seek is what I like to call the cognitive opiate of the flow. There are a lot of opiates we can put in our veins. There's only one opiate we produce in our brains. And that's that extraordinary feeling of being completely absorbed in something outside ourselves. When you're hanging a show, right? It's that feeling right day after day. And, you know, you lose, literally lose track of time because it's so absorbing when I'm in the middle, of an essay. But the great thing is, is that if you give yourself over to a new activity and you pursue it with passion and perseverance, even if you never get any good at it by an external standard, you still have access to that cognitive opiate. You still have access to the flow and to that absorption. I have never been happier in my life than I am when boxing badly. And that includes writing well, I write well and I box badly, and they both make me about equally happy. In fact, the boxing makes me happier because when we do something well, we do something as a vocation, we can only be aware of the space between our original ambitions and our actual accomplishments, so that when I'm writing, I'm thinking every sentence is going to have the psychological intricacy of Proust and the sensual rhapsody of John Updike and the malicious wit of Jane Austen. And it doesn't, I don't I never quite get all the sentences that good. And that's all I see. I never take pleasure in my own writing for that reason. I take pleasure in doing it, but not in reading it. But when you're boxing, you can say, boy, I really threw that jab today. Better than I've ever thrown in. All right? Opened up my shoulder to throw the cross better than I ever have. It would not knock out a mouse from the mouse was there. But the potential. And my favorite chapter in the book actually is, is about that. Because, you know, I pursued that old folk tale that hummingbirds and elephants have the same number of heartbeats in a lifetime. They, you know, you've all heard that, right? That, that and that turns out to be true. There's a research project at North Carolina State University called the Heartbeat Project. And they just collate the heartbeats of mammals and birds. And it turns out, grosso modo, that almost all mammals and birds have a billion heartbeats in a lifetime. The hummingbird expense her heart beats in 100 days, the elephant in 100 years. But the the the metaphoric leap you have to make from that is that the hummingbird doesn't feel that she has less of existence in her experience than the elephant does, and we can judge ourselves by our interior hummingbird heartbeats as naturally as we are judged in the outer world by the the the exterior elephants of of excellence. And so this is a long winded way of saying that there is a limitless rewards in pursuing new accomplishments in later life, that you will always do badly.

GLORIA GROOM: Well. And I love the fact that you always do badly well, that's optimistic. I love the fact that in this world of remote learning and, you know, and every can you can learn by YouTube, you can, that you went out and sought people that were really, really good masters of what they do because you were interested in the learning, but also the relationships. And it sounds like you kept these relationships like these are not just, I'm through. These are people you're going to see again.

ADAM GOPNIK: No, we had a party in fact. I didn't want to have a book party because book parties are inherently sad because everybody's, fingers crossed, hopeful the book is going to do well. So we decide to have a book party after the book was already a failure when we could just enjoy it. And but we brought together all of the teachers from the, from the, from the book, and because they had not known each other.

GLORIA GROOM: Including your mother.

ADAM GOPNIK: Included. Well, unfortunately, I couldn't bring my mom along. She's not she's she's not as well as I as I wish she was.

GLORIA GROOM: She was there.

ADAM GOPNIK: But she was there. Oh, my God, my mother's there every minute of my life, hovering over my shoulder and telling me, dear, dear, you can do that

better.

GLORIA GROOM: That's where it started.

ADAM GOPNIK: No kidding. You want to, excuse us. We maybe need a psychoanalytic session here. But it's true that my my mother is an extraordinary woman. She was a great cook and a great baker, and none of that was what she did professionally. She was a linguist, scientist. And, there's a whole chapter about learning, going up to learn to bake with her, which I never thought Gloria, but and now that I stop to think about it, it's very much like the chapter about dancing with my daughter. It was a way of having a conversation with my mother, who's a brilliant, but somewhat difficult woman. And we are very much alike. And we, we're, you know, loving but could have complicated exchanges. And I thought, well, I'll just go up and bake with her and we'll just have our hands in the same sourdough starter. And that turned out to be very worthwhile. And also, it was revelatory for me because, Martha, my wife, I had totally forgotten, was a baker when we first met. She baked her own bread, but it got kind of so lost in my mother's very extravagant and ostentatious world of showy baking that her little loaf got, I had amnesia about it.

GLORIA GROOM: She got out-loaved.

ADAM GOPNIK: He got out-loaved, she got out-loaved, and I had to be reminded that she was not a loaf, but a baker, which is a valuable thing for for a husband of many years.

GLORIA GROOM: So I think we should probably wrap up and ask some questions of Mr. Gopnik.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: Hi, Mark Siegel. So you talked about baking. I'm more of a cook than a baker. Although I've started, tried to master pizza making at home. But I'd be interested. I've heard you on a lot of food podcasts, and I'd be interested in what you see, if any, as essential differences between baking and cooking. Particularly along the sort of the lens of mastery that you've worked on, other than you tend to focus on using a scale in baking more than in other cooking.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yeah, it's a great question. In simple in, in plain English. Right? Cooking is, improvisational and baking can't be right. And that's hard. So I love cooking, right? Because you always can, you know, you add a little something extra if you're if you're a little bit off, if you have a, you know, if a recipe calls for a quarter cup of white wine and you have you add half a cup, or you don't have a quarter cup of white wine and you use, vermouth, you can make out, you can play with it. You can't do that with baking. Baking is essentially a chemical transaction, and it suits people like the French who are very rigid in their in their habits. Right. And, I, I'm a natural cook in that way. For me, cooking is the release, and I cook almost every night because I'm locked in my head in, in the precision of words. And then I come out at night and I can escape into a physical precision of chopping onions, but also into the freedom of doing things. So baking for me is kind of, antithetical to my nature, but I still try it. And my mom taught me how to make the "broissant," which is her own invention. It's a cross between a brioche and a croissant. And this will tell you something on in one of these colloquies when I was blessed with an interlocutor like Gloria. It was Malcolm Gladwell. And Malcolm said to me, how could you let $1 million just fall in the floor? You should be opening "broissanteries" all over America where you have "Mom Gopnik's Broissants" right? This is the difference between my dear friend Malcolm Gladwell and myself.

GLORIA GROOM: Just want to interject here. We've done a lot of French shading, but both of us love the French and we're both les gens d'honneur.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes.

GLORIA GROOM: Just so you know that we're both wearing proudly our little.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes. This is the only time where you will see, two people with the les gen on them, their lapels or not? The only time, but a time.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: My name is Mark. And first of all, thank you very much for coming out and sharing your experiences. My question, ironically enough, concerns the French language and mastering the French language. My personal experience I studied in high school and in college. However, it wasn't until I joined the Peace Corps and served as a volunteer in Chad, Africa. And the bottom line is my question is, what was your experience with learning the French language? Mine was the breakthrough occurred when I lived in Chad and and had to speak French in order to obviously communicate with others. I'm curious as to whether or not you feel the immersion process to learn a language is critical. And thank you very much.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yeah. You know, I grew up in Montreal, Canada, which is a French speaking city, obviously, and I learned hockey French. I learned all the vocabulary of ice hockey, which is the religion, the national religion of Quebec. And, so that was not very helpful in France, the, the having a very advanced vocabulary for talking about ice hockey. But you find. Yes, exactly. Immersion matters and the and the, the two things that will produce excellence in language learning are eroticism and emergency, and the two can be linked. The way to learn another language is to fall in love with someone who only speaks that language. Like, you know, the Beatles. Great song, Michelle. Right? You know, he's that's how you do it. And the way that my wife and I realized that we had finally, after six years in the country, we were not that bad in French was exactly when Olivia was being born. And she got turned around, as happens to babies. And we had to make the decision that it was Martha's decision. But obviously I was there. On whether or not to wait to see if the baby would flip again or to do an emergency cesarean. And after much back and forth, they decided she decided, let's do the emergency cesarean. Fine baby. Everything was great, and it was only a couple of days later that we looked at each other and that we did that whole thing in French, right? You know, Qu'est-ce que vous on sait madame. C'est une bonne idee de le faire ou pas. And we just did the whole thing in French without even stopping to think that we were speaking French. We just did it. And that's still the height of my of language.

GLORIA GROOM: So hopefully a conversation you don't have to have again.

ADAM GOPNIK: Yes. We never will have again, but it was the proof. So create an emergency or find an erotic relationship.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3 I'm Dean Buccola, I'm Chair of Humanities at Roosevelt University here in Chicago. And I just thought, while we're here with Chicago Humanities in this church of the humanities, if you could speak a little bit to the way in which at least I feel the humanities are sort of under siege right now with backlash against higher education and book bans nationwide, etc...

ADAM GOPNIK: I would love to and and it's a pleasure to meet you. I, I had once did a lecture at Roosevelt on Galileo and Shakespeare, and it was one of my I've worked hard on it and it was something I do even better lectures for Gloria. But I mean, it was a good lecture.

GLORIA GROOM: Thank you.

ADAM GOPNIK: It was a good lecture. And I love doing it. And I love the environment. Yes. Let me speak to this because I feel passionately about it. One of the points of the book, which I actually wrote about overtly in the first draft of the introduction, and then was persuaded by my editor to delete because it seemed to, what's the word too, inside baseball, in a way. Was that one of the things that this book is about is the superiority of the humanities to the social sciences. Because you will find it, you will find a lot of people, you know, a lot of this book is about material that very much is the domain of the social sciences. Right? How do we learn things? How do we know things? What's the what are the, what goes on in our heads? What goes on in our lives? What's the social psychology of learning all those things? And that's all valuable and useful and so on. But the point is, is that in real human lives, there are so many vectors pressing down on everything we do. And that's what I was trying to that's what I'm trying to say in this book. You can't extract out the the cognitive psychology of learning from the social psychology of family relations. And you can't, extract out the social psychology of family relations from the intimate psychology of, of sibling relationships. And there will never be a science of family. There will never be a science of siblings. There will never be a science of storytelling. There will never be a science of love. Not because these things are ineffable or mystical, but exactly because they are so deeply human, which means simply so susceptible to so many vectors at the same time, that the only way we can explain them and talk about them adequately is through the humanities. Is through essays and stories and novels and songs. That's the material by which we come to understand the most difficult things we do in life. So this book is meant to be a vindication of the superiority of the humanities, to explain the things that matter most to us in life over all, anything you can study in a STEM program. Is that a place to end?

GLORIA GROOM: That's a beautiful place to end. Thank you so much.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Adam Gopnik with Gloria Groom recorded live at Chicago’s Epiphany Center for the Arts in May 2023. Check out the show notes for more information on Adam Gopnik and his recent book Real Work: On the Mystery of Mastery.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with help from the team at Chicago Humanities for the programming and production of the live events. Head to chicagohumanities.org for more information on how to catch your favorite speaker in person the next time they’re in town. New episodes of Chicago Humanities Tapes drop first thing every other Tuesday morning wherever you get your podcasts. If you like what you hear, give us a rating, share with your friends, and scroll through our incredible backlog of programs to discover a gem that might surprise you. We’ll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode for you, but in the meantime, stay human.

GLORIA GROOM: You said you took up boxing because of Trump. If things don't go as well as they should, what will you take up?

ADAM GOPNIK: Learning Italian.

[Cassette tape player clicks close]

SHOW NOTES

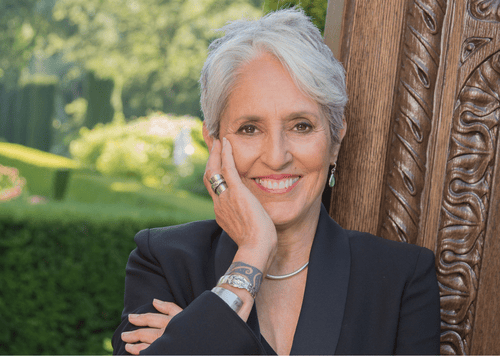

Gloria Groom ( L ) and Adam Gopnik ( R ) on stage at the Epiphany Center for the Arts at the Chicago Humanities Spring Festival in May 2023.

Adam Gopnik, Real Work: On the Mystery of Mastery

Adam Gopnik, Paris to the Moon

George Plimpton, Paper Lion: Confessions of a Last-String Quarterback

Read:

Adam Gopnik, Last of the Metrozoids

Explore:

Bruce Nauman, “Clown Torture”

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- September 26, 2023

Patti Smith Reflects and Lives in the Moment

- Podcast

- May 16, 2023

Jessica Lange Captures Truth in Photos

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!