Halloween Special: Morticians, Witches, and Ghost Stories

S2E4: Caitlin Doughty with Mark Bazer, Kristen J. Sollée, Amy Giacalone

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

We have three tales of intrigue from the dark depths of the Chicago Humanities annals, featuring selections from YouTube’s Caitlin Doughty of “Ask a Mortician” about if cats will eat your eyeballs when you die, New School faculty member and author Kristen J. Sollée from her lecture “Witches, Sluts, Feminists,” and a section of a short ghost story by Chicago author Amy Giacalone from the compendium “Ghostly,” compiled by author Audrey Niffenegger.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Your cat doesn't want to eat you. But if you have not been found for several days after you die, they're going to do what they have to do. The dogs will also eat you.

KRISTEN SOLLÉE: In a way, magic is really a metaphor for feminism,

AMY GIACALONE: So I was sitting in the bath, and that's when the tiny ghosts start showing up.

[Tape cassette sound]

[Theme music plays with theremin sound effect]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hellooooo. And thanks for checking out Chicago Humanities Tapes, we are the audio arm of the Chicago Humanities live Spring and Fall Festivals. Haaaappy Halloooweeeen. Ok if you couldn’t tell, it’s my favorite holiday, second only to Tu BiShvat, and my birthday.

Today, we have three tales of intrigue from the depths of the Chicago Humanities annals, the dark cassette tape web if you will, to bring you the spoookiest, the eeeeriest, and …a couple of really gross sections… that the archives have to offer.

We’ll hear from YouTube’s Caitlin Doughty of “Ask a Mortician” about if cats will eat your eyeballs when you die, and New School faculty member and author Kristen J. Sollée from her lecture “Witches, Sluts, Feminists,” and finally, a section of a short ghost story by Chicago author Amy Giacalone from the compendium “Ghostly,” compiled by author Audrey Niffenegger.

I have actually met one ghost (that I know of) - ok so my last apartment building was definitely haunted. I was unlocking my bike from the bike room in the basement, the sun was still out, but there’s one lightbulb in the ceiling that’s flickering on and off on and off. so aggressively that it makes it hard to see what I’m doing I made a mental note - when I get home later, I’ll email my building, someone will come and fix it. I get back late that evening, when it’s pitch black outside. The light is still flickering so intensely on and off on and off. I think to myself, I wish it would stop doing that, it’s so hard to see what I’m doing! And in that exact moment, the light STOPS, and is just, on. I know you can talk to ghosts, so I say out loud, “Thank you!” and then it GOES OUT INSTANTLY. I’m not kidding. I run back up to my apartment “no no no no no” and the light next to my door is ALSO FLICKERING on and off on and off. I turn it off and sleep with the rest of the lights on.

It turns out I’d moved my bed recently and just messed up the flow to my room or something and the ghosts were all mad about it so I just put it back and everything was totally fine.

And now, if you’re not too scared, onto our regularly scheduled program.

First up, Caitlin Doughty of “Ask a Mortician” as interviewed by Mark Bazer of “The Interview Show” at Chicago’s Field Museum in Fall 2019.

[Theme music]

[Applause]

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: the title of the book, "Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?" actually comes from an event that I did in Australia. And a young boy, probably 11 or 12, raises his hand, asks that question, and immediately a light bulb just went off in my head that it's just such a brilliant way to ask that because a lot of people in this room are sort of wondering in a more dark, existential way what will happen if they die alone and no one finds their body and they have these cats? And what does that mean and what's the facts?

MARK BAZER: Only kids, I feel like, would ask, “What happens when cemeteries are full?" "What happens if I die right after I've eaten a bag of popcorn and I then get cremated?" Like when are kids asking you these questions? Do you go up to kids at the mall?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Yes, they're all from when I went up to children at the mall. I'm like, "Hello, Sonny, I'm a mortician. What corpse questions do you have?" But here you have this 12 year old who's like, "hey, will my cat, if I die, will they just start eating my eyeballs?" And that's almost—even for adults, that's a friendlier, more accessible way into that question. And that was kind of the premise of the book, is: can we go back to these very pure questions that aren't—that don't necessarily have all of the layers of adulthood that most questions about death have.

MARK BAZER: They wouldn't go right for the eyeballs first, they'd eat the softer parts of your body.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Exactly.

MARK BAZER: Yeah.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Yeah. You know, um, they [laughing] so—

MARK BAZER: Well, I've asked my cat.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Yeah, exactly. "I talked to my cat about that." Talk to your cat about these issues. It's very important. So the answer is that your cat doesn't want to eat you, your cat wants its food. But if you have not been found for several days after you die, they're going to do what they have to do, which I sort of admire as a trait and relate to. So they will come to your body, and they go for more exposed parts, your lips, you know, around your nose, your eyelids. They may eventually get to your eyeballs, but really they want the soft flesh, easily accessible flesh around your face.

MARK BAZER: So reading the book, I kind of felt like cats were getting the revenge. Because you also mentioned that people in Europe hundreds of years ago used to put cats in the walls.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Yes, like potentially living cats. So it was it was almost like a witchcraft thing. Like if you—if you sealed cats up in the wall, it would protect you from witchcraft. But they had a lot of things that they thought would prevent you from witchcraft.

MARK BAZER: And none of them did.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: None of them—well, you know, there was no witchcraft, either, so.

MARK BAZER: So no reason to store the cats in the wall, and then they would later get revenge by eating your eyeballs.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: The dogs will also eat you. But allegedly, or from my understanding, from the research, it's much more because they are very anxious and they want to—why is that funny? They're anxious.

MARK BAZER: Well, they're worried about their owner.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: They're worried about their owner!

MARK BAZER: Whereas cats don't give a sh—

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Whereas cats don't care. And someone was like, "Oh, that's evidence that, you know, dogs rule and cats drool." And I don't agree. I think that the cats, again, are doing what they have to do. They're not emotionally caught up in attachment issues. They're just like, that's the kind of independent woman I would want to be. So I appreciate cats' behavior around your dead body.

MARK BAZER: So let's get into the why kind of behind the book. The book is fun. And you talk, you say, I think there's a line in there that says something like death itself is not fun. But learning about death should be fun. What is driving your advocacy?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: I mean, the advocacy for me has really become a couple of things. It's humans should interact more with their dead. They should be more present and more responsible around their dead. And I don't mean necessarily like forcing you to take care of your own dead, but knowing that you have those rights and that you have the ability to do that and handing the bodies straight off to the funeral industry like at it's emergency is not necessary. Second thing would be new green options and new technology around death like an acclimation, like recomposition, like natural burial, which is not new but is in fact old. And just going back to natural burial fans. Every one of these new things.

MARK BAZER: So what is natural burial?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Natural burial is incredibly simple. It's the idea that most American cemeteries over the last hundred years or so have developed a way to keep your body nowhere near the earth around it. So when we talk about burial, we're really talking about burial because the body is going way far under the ground, in a concrete vault, in a sealed metal or wood casket with a chemically preserved body in it. So it's layers and layers and layers of protection around this dead body. Whereas natural burial, for me personally, it's what Jewish people what Muslim people have been doing the whole time, which is just a shallow hole in the ground, usually about three or four feet deep where all the rich decomposition soil is and the fungi and the bacteria and the things that decompose you and the body in a simple unbleached cotton shroud and allowing your body to decompose quickly and efficiently and really go back to the earth where we came from. So for me, it's really an explicit statement of I accept and celebrate the idea of my decomposition. I think of myself as a creature of the world that's made of organic material, and I want to become organic material again when I die. So it's a really different mental way to think about what is done with your body, whether you want to highly preserve it and highly protect it, or if you're like, tear me up, bacteria, tear me up fungi, I'm ready to go back into the earth. And so promoting those things and also just a general cultural engagement with death, which is a lot of what this book is about. And we talk about death denial. Academics don't like it when you talk about death denial, because denial isn't really what's going on. And some people don't have the privilege to deny death. And that's all entirely true. But when I talk about denial, I'm not only talking about potentially the denial that you experienced in your household growing up around death. I'm also talking about the overall cultural denial around death and the way that we don't allow for different experiences and different religions and different. Cultural groups to express themselves in their death, in their death traditions, because we have a very aggressive, expensive cookie cutter way of providing people with death services in the United States.

MARK BAZER: Let's pivot. One child asks: "We eat dead chickens. Why not dead humans?" So what's—what's wrong with cannibalism?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Nothing! Honestly, nothing is wrong with cannibalism. I mean, like murder cannibalism, not good, but—serial killer cannibalism, not preferable. But as far as cannibalism, there's—throughout history there have been so many different groups that practice what we call mortuary cannibalism, which is something that I've long been fascinated by, which is the idea of basically eating your own dead in a ritualistic way. And the thing that really blew my mind open was the story that I told in "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" about the Wari' tribe, and they're a tribe in in very rural Amazonian Brazil. And what they would do is—not the immediate family, but they're called affines. It's the sort of, you know, your aunt, your uncle, your cousin. The slightly second level of family would, as a favor to the family, come in and eat the dead body of the person who had died. And it wasn't like yum, yum protein because as I learned while researching this book, we're not good protein, we're not good eating. Humans are not like the reason that cannibalism probably hasn't developed as much as it could have is that we're just not nutritionally sound.

MARK BAZER: Can you imagine, though, how awful it would be if we were and tasted great?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: It would be a whole different world that we lived in. But there's just so many calories—like we don't have a lot of calories to offer. We're just not good eating. So, it wasn't great for these—for these people. It wasn't like mm, yum, a dead body. It was actually pretty, pretty disgusting because the body would already be decomposing a little bit. It made them a little sick. But it was so important to these tribes to almost subsume the person back into their group. And the person who died, they would also tear down the house that they lived in because it meant that the family now had to count on the community. It was almost forcing the person to depend on the community around them after someone dies, which is a beautiful thing when you compare it to how lonely death can be in our culture for a lot of people. Your husband dies, you get three days off of work.

MARK BAZER: You get three days off and you can eat your husband.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Yeah [laughing]. You know, I don't—I question whether we're ready for that as a culture, but there is something radical in that. The idea that, okay, now you are—we're throwing you back in to be completely dependent on the community and the community has to rally around you to the point that they're literally eating your husband.

MARK BAZER: Yeah.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: To bring you and him back into the community and that—the reasons for that completely changed my idea about what cannibalism is and why it was done. And there are many cultures that—that practiced mortuary cannibalism, and usually it was colonized out in some way. But I think that—I don't know. I think it's—I think it's. It's taboo for many reasons, but I think that it's underappreciated as a death ritual and something that was, that was very valid for many people.

MARK BAZER: So here's another question that I loved, which is: "when you die, why do you turn many colors?" And what I didn't realize is: you really turn every color. [14.1]

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: You do. And I think when I first started working in a crematory, when I was about 23 years old, I knew that people, when they decompose, they turn colors. But I didn't understand the vividness of the colors, the vividness of the aquamarine color that your lower stomach will turn as the bacteria are chomping away on your insides and they're farting inside of you. Because that's what bacteria do, is they eat you, they excrete and fart and you bloat up and you turn this – You –

MARK BAZER: You call them bacteria farts.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: I call them bacteria farts because that is scientifically what they are. We perceive the body as being dead and the person—you yourself—are, in fact, dead. But there's so much happening inside of that shell with bacteria, with, you know, the decomposition, with the blood vessels decomposing and blood being released and staining the body. Don't think that decomposition happens immediately because that will prevent you from maybe staying with the body or taking that time that you need. Decomposition is starting to happen immediately after someone dies, but it's a very slow process that will take several days or honestly, probably about a week to get to these strong color combinations that we're talking about here.

MARK BAZER: So you've seen this?

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: Oh, yeah. Well, yeah.

MARK BAZER: You've seen all the colors.

CAITLIN DOUGHTY: I've seen all the colors. Yes. They turn this—your stomach just turns this glorious aquamarine color, just absolutely gorgeous, like a Grecian sea on a—on a like, calm day.

[Applause]

[Theme music]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: For more information on Caitlin Doughty, head to chicagohumanities.org for the show notes, including links to her YouTube channel and book Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs? and Other Questions About Dead Bodies. Next up, Kristen J. Sollée on witches, sluts, and feminists at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in Fall 2018.

[Theme music]

[Applause]

KRISTEN SOLLÉE: Thank you. I'm going to be speaking about the origins of the witch archetype and the ways the witch archetype has been harnessed for political action over the past hundred years. If you've been noticing the witch has been really having a moment, film and television are filled with tales of witches and otherworldly women. Visual art and literature are plumbing the depths of pagan lore. And runways are replete with occult symbolism. But at the same time, and no coincidence is at the same time a new wave of feminism is cresting. Some are calling it the fourth wave. Some are calling it late third wave, whatever you call it. With the MeToo movement and the women's marches around the world, systemic sexism is being addressed like never before in the mainstream media. And for many of us in our own personal and professional lives. So in this context, I believe that which is in feminism right now are rising together for a reason and to understand the sexism women and folks on the feminine spectrum face today and the cultural response to it. Examining the misogyny that drove the witch hunts centuries ago can help illuminate its brutal origins and perhaps even offer liberation from this cycle of abuse. It's really become de rigueur to talk about feminism and women's rights using the witch archetype, so much so that it's almost commonplace. I feel like I'm saying obvious things now, but that is not always been the way so many may now embrace the which is a symbol of empowerment, especially those dubbed Generation, which by ID magazine, which is basically anyone under 40 right now, but for centuries. And in parts of the world today, women did suffer and die as a result of their perceived association with witchcraft.

Why are we here talking about witches? Because we love witches. And obviously there's a whole other discussion to be had about witchcraft practices and pagan practitioners, but this is mostly about the archetype, so. The woman who's responsible for sort of rescuing the witch from this brutal history is Matilda Joslyn Gage. She's an abolitionist and a suffragist. She wrote "Woman, Church and State" in 1893. And in it, she basically unmasks the European witch trials for what they were: an attempt by the, you know, the Catholic Church for a power grab, and local communities as well. And again, scapegoating the most marginalized people for a variety of reasons. And she writes "a witch is basically a woman of superior knowledge. And in looking at the history of witchcraft, we see three striking points for consideration. First, that women were chiefly accused. Second, that men, believing in women's inherent wickedness, and understanding neither the mental nor the physical peculiarities of her being, ascribed all her idiosyncrasies to witchcraft. And third, that the clergy inculcated the idea that the woman, that woman was in league with the devil and that strong intellect, remarkable beauty or unusual sickness were in themselves proof of this league." So unfortunately, it wasn't her writing that changed everyone's minds because a lot of people weren't reading this. She was actually kicked out of a lot of suffragist circles because she was so radically anti-Christian. But. Her son in law was L. Frank Baum. Yeah, right. And he was deeply inspired by the way she reframed this archetype of the witch and therefore roped a good witch into "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" which is published in 1900. And then fast forward to 1939 and the whole world, with the MGM film, saw that yes, indeed, there could be good witches and bad witches. So it's the work of Matilda Joslyn Gage that opened our minds to some of the lies that we had been fed.

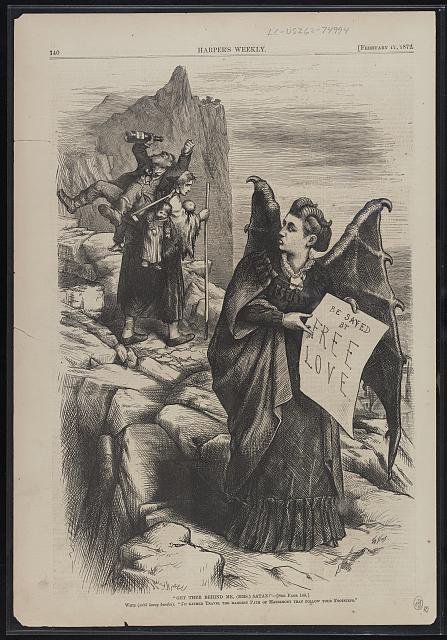

Then there's another fun suffragist of the period I just want to mention, because she's so fantastic. She was a suffragist, free love and reproductive rights advocate. Victoria Woodhull was also the first woman to run for president in 1872 on a ticket with Frederick Douglass. She was a sex worker and a spiritualist medium, and she launched the first American newspaper to print the Communist Manifesto. And, of course, she was called "Mrs. Satan" for her views.

So after "The Wizard of Oz" you begin to see a smattering of good witches in film and pop culture, or at least slightly naughty witches. Not just fully evil, hideous witches like Veronica Lake's character in "I Married a Witch" from 1942, Kim Novak's character from "Bell, Book and Candle" in 1958, and then we have Samantha from "Bewitched." And, you know, I wasn't always a fan of "Bewitched" but the deeper I looked into this history and the way you could tie it into the harnessing of the witch archetype for feminist action, I started to change my mind about her. So "Bewitched" first airs in 1964, a year after Betty Friedan's "Feminine Mystique" is really galvanizing the women's liberation movement, and a few episodes are even written by a self-professed feminist TV writer, Barbara Avedon. And like "The Feminine Mystique", "Bewitched" addresses the plight of the white middle class housewife. And it may not seem like it, but in a way magic is really a metaphor for feminism.

In the show, if you haven't seen it, Samantha is a witch, and her husband Darrin hates that she is a witch and has these powers and he's angry and he says, "please don't use these powers, like it freaks me out that you have this." And it's clearly because he's threatened by her having this, this agency outside patriarchal structures, outside the marital structure. And throughout the series, she uses magic to help herself and him. And in that sense, there is sort of a radical underpinning to this show. But, witches get way more radical, of course. In the late sixties, we have the Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell. So they were formed in New York City on Halloween in 1968. Robin Morgan, Florika, Naomi Jaffe, some of the others names have been lost to history. But they set their sights on capitalism and corporations. That was the engine driving sexism of the day. And they put on these guerrilla theater protests. They dressed up like witches with their capes and their brooms, and they really harness the witch archetype for serious political action. And they hexed the New York City Stock Exchange, protested a bridal fair, sent hair and nail clippings to a university that fired a radical feminist professor. And they came up with slogans like this, which sounds like something you'd find today in a teen magazine. Like this is—this is the kind of—this is kind of, you know, the the mood of the moment. And this was just a palate cleanser. But I actually was pretty happy with Elvira the other day when she encouraged her fans to vote against racism and sexism, xenophobia and the midterms. So, you know, Elvira's like starting to become an activist herself, I guess.

Let's go to the next really important moment in the legacy of witch activism, and that comes in the eighties with Maryse Conde. And she wrote "I, Tituba: Black Witch of Salem" in 1986. And just as "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz" reframes popular perceptions about who witches were, so did this book, which was using racism and sexism in the Puritan era to talk about racism and sexism in the eighties. And Angela Davis in the introduction to the book, affirms the importance of Conde's creative work as activism. And she writes: "Tituba engages in recurring meditations on her relationship as a black woman to feminism, and her voice can be viewed as the voice of a suppressed black feminist tradition, one that women of African descent are constantly reconstituting in fiction, criticism, history and popular culture." So here we have the image of the witch further broadened, so much so that there are a lot of people, I believe, that think this book is a historical work, and I meet people all the time that tell me things and I'm like, no, we don't really know much at all about Tituba from historical records. If you remember your middle school history about Salem, she was one of the first three women accused of witchcraft. But this really rescues her tale from the refuse bin of history, as it were, and, you know, makes a lot of important points about contemporary society and the process.

I'm going to go back a bit. There is one central theme. As the German historian of the witch hunts, Lyndall Roper says, that, um—"The themes of the witch trials recur with monotonous regularity across Western Europe," she writes, "featuring sex with the devil, harm to women and childbed, and threats to fertility. All issues which touch centrally on women's experience." So popular narratives of the witch to this day reflect narratives about female power and female desire. So there are three types of women who are most likely to be witches, according to the Malleus Maleficarum. And they are midwives, adulteresses and fornicators. So the midwife, because they're dealing with this mysterious liminal space between birth and death in sickness and health, and they specialized in the needs of women, they were viewed as suspect not only by the church and state, but also by patients and their families. So if an an ailment wasn't healed, it was witchcraft. And if an ailment was healed, it was witchcraft because God would not grant healing powers to peasant women. So witchcraft was blamed for heal or harming, as I mentioned, and women caught performing abortions, which is often what midwives did, could be deemed witches and accused of witchcraft. And they were also considered so dangerous because they were countering a culture of misinformation about female bodies. Not that they also didn't use spells and charms and other things we would find to be incredibly detrimental to our health today. But there's also the argument that most people didn't believe that midwives themselves were the servants of Satan, but they were just so much a threat to the male medical religious establishment that it was an easy way to discredit them, to associate them with Satan and sorcery. So it remains to be seen exactly what is the case. We don't know exactly how many midwives are put to death versus other women because a woman's occupation was not recorded before she was put on trial or executed. So these are, you know, slippery documents these historians are working on when they're going into the annals of the witch hunts. So witch hunting, of course—I'm going to go forward a bit to go back—became, um, it waned throughout the Renaissance era, pretty much ended by 1750, so that's even pre-, and midwifery became progressively licensed by the state. But women are still consulting midwives for abortion, contraception, and fertility and midwives did come into conflict with the mainstream medical establishment, particularly during the New England witchcraft cases. And according to Sylvia Federici, my favorite Marxist feminist, the early modern witch hunts and the work of the midwives are linked to the contemporary development of a new sexual division of labor, confining women to reproductive work. And this sexual division of labor, I would argue, largely remains intact. And the women who seek to undermine its supremacy by exerting control over their own reproductive function are often viewed through the same lens accused witches once were.

How different are today's sluts seeking birth control and basic reproductive freedoms than the satanic witch midwives of yesteryear?

[Applause]

[Theme music}

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Kristen J. Sollée. Head to the show notes for her book link Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive, and some accompanying images from her lecture.

Last up, we have a portion of the short story “Tiny Ghosts” by Amy Giacalone, from the compendium “Ghostly,” curated by Audrey Niffenegger, and recorded live at the Poetry Foundation in Fall 2015.

[Theme music]

[Applause]

AMY GIACALONE: This is from a short story called Tiny Ghosts. So I was sitting in the bath when the tiny ghosts started showing up. And I'm not going to tell you anything too specific about my bath because I don't believe in pornography. Because right away you're thinking it's bubbly and sexy and ooh la la. But that's not the kind of bath I take. I take oatmeal baths. You can buy the oatmeal bath packets from Wal-Mart for $4.99 on sale. They come in a box of eight, and Walmart's all that's around for shopping. So I take an oatmeal bath with Epsom salts for my arthritis and the colors, the water is the color of street slush in the winter. Little globs of oatmeal float around sometimes, and I smush them in my fingers. It's weirdly satisfying, and I don't mind mentioning it. I take my baths in the upstairs bathroom, which is not attached to the bedrooms since it's an older house. I light a candle that smells like peach pie. I pour myself a cup of wine. I don't like wine glasses. Too delicate. So it's just in a cup, which is good enough for me. We buy Sutter Home White Zinfandel, which is $3.50 a bottle. In town. We can get it from CVS for $4.99. That's why we really do have to drive out to the Walmart. It's like that with everything. I like my bath water really hot. As hot as I can get it to go. I have my bath copy of Jane Eyre. The good copy is that hardcover. And this one's a fat paperback. It's got wobbly pages from the bath water. I never start at the beginning of it anymore. Not particularly. Usually I just flip to any spot I feel like reading. It's a very complicated book, and I'm proud to say I've read it many times because I'm a good reader. My bath is comfortable and the room looks nice because I have a very nice house and I can't help but notice for a second that things are perfect. You know, you have to work hard all the time just to get things perfect for even a second. It's very satisfying to be me. Well, I'm only about halfway through my bath night when my husband Gary gets home. This is still before the tiny ghosts now. And I hear him come upstairs and he just comes in like he does. He opens the door and I pop straight up in the bath, and he comes over and kisses me on top of my head. He has to bend all the way over to do it. And then we start to talk. Hey. Hey. How was your night? Good. Yours? Well, it's still going on. I have wrinkled hands always, but especially now from the bath water. So I reach over for some wine and he says, "Mind if I pee?" And I say, "Yes, sure." And I pull back the shower curtain while I take a sip so that he has his privacy. "You're reading Jane Eyre again?" Gary asks. "It's my favorite," I tell him. "Huh?" He says. "I was just talking to Pete. Now he's a guy who really knows how to read. Reads a book a week. Big ones, too. Very impressive." Now it's pretty nice with the curtain pulled dark. It's like a tiny room, that's all baths. Which is an idea I don't mind saying I like. I picture myself in the tiny room, and I wonder how I'd get into it. Probably a tiny door. Tiny door? Sure. A tiny door. And then I see myself very tiny. And I get in through the tiny door and I dive right into the bath. Gary flushes. He washes his hands. He pulls back the shower curtain and then I'm my real size again, he picks up my book. "Pete should read Jane Eyre," I say, "because it's a great book. Anyone would like it." But guess what my husband says. "Neh. He only likes new books, hip ones." "Jane Eyre is a hit book". "Oh, I know that," Gary blushes. And now, of course, he's backtracking. "That's not what I meant. I meant, like, whatever the newest book is on the new book list." So I say, "Hm!" which is what I think of that. And I say, "You know, I'm trying to enjoy my bath." Gary comes over and kisses me on the head again. "Okay. You know, I didn't mean that about your book. I'm sure Pete would like it a lot." And then he leaves and he didn't mean it, but he made me feel like an old fuddy duddy sitting in the fuddy duddy bath with my fuddy duddy bath book. And that's when the tiny ghosts start showing up. First, a tiny door opens up. The tiny door's in the corner by my feet, where the tub meets the wall. And there's a tiny ledge. It's not like a fancy door, just a regular brown door with a knob. And a little person walks out and he just stands there. He's kind of clear, like a shadow, and he's wearing cargo shorts, flip flops and a T-shirt, maybe the size of my hand. He has tiny black hair and a tiny beard. He's carrying a tiny towel. Of course, I pull my feet back fast, which splashes, I cover up my chest area with my knees. I think I'm probably imagining things, but I'm a pretty steady person. And it isn't like me to imagine this hard. And he talks to me. "Oh, hey." He holds up one hand. He's waving. He looks around. "Hey?" I say. I'm holding my two knees tight. "What are you doing here?" He asks, like I'm interfering with his night and not the other way around. So I go, "Taking a bath?" He doesn't say anything, just puts his hands in his pockets and nods. "Okay," he says, and turns back to the door. "What are you doing here?" I ask pretty quick, since I want to know and I think he's leaving. "I thought I'd take a bath. Didn't know you were still using the tub. I'm sorry, what?" "Baaath," he says slowly, like I'm stupid. And he makes a circle with his hand indicating the tub I'm sitting in. "But it's no problem," he says. "I'll come back later." "What?" "Seeya." I talk fast. "I'm sorry," I say, and I hesitate at what I should call him. Mr.? Sir? Little guy? So I go with, "I'm sorry, you there. You're a - not to be rude, but what are you?" "Ghost." "A tiny ghost?" "No, a big one, asshole." "Excuse me?" "K, bye." He waves again and goes out the tiny door and I'm alone again. "Wait. What?" I lean over and open the tiny door, which is still there. But the ghost is gone. I'm all thumbs because the doorknob is so tiny. And for a second, I think that maybe my hand will go right through it if it's a ghost door after all. But no, I open it just fine and I have to lean all the way over to peek inside. All there is is a long, black, tiny hallway. It's cold in there. I can feel a little chill coming out. So of course I shut the little door and get my butt out of that bath. I wrapped myself in two big towels when as a dress and the other, I twist my hair up in, but kind of crazy since I'm shaking all over. I flip on the light switch. I blow out the peach pie candle. And "Gary!" is what I start yelling. He's yelling too. "Hey, hey, yo, look out. Angie, where are you at?" I hear his footsteps coming toward the bathroom. I open the door and we almost smack right into each other. We're going so fast. "Honey?" he says. "I think I'm hallucinating something." And then we both start babbling and waving our hands, and we're saying the same thing. Gary's going on and on about a tiny door and a tiny ghost, too. So we set up all night together right in the middle of the bed. We can't fall asleep. We don't even try to talk to each other. We just sit and stare out in different directions. Soon we're laying down, but it's laying down like a couple of kittens. In the middle of the bed, all curled up around each other. At about 2:00, I get hungry. I don't put my feet on the floor because I'm afraid a tiny ghost is going to scurry out. I bend down by my nightstand and open the bottom drawer on it. I keep a box of saltines there. "Don't drop any crumbs," Gary says. "Huh?" He shakes my saltine box. "Crumbs will just attract them." "Like with mice?" He shrugs. And I have to admit, in my mind, it's like we have mice instead of tiny ghosts, too. Then again, maybe the saltines do attract them. I don't know, because a tiny door opens in the bedroom right above Gary's dresser. A little brown door, and out comes six, six tiny ghosts. It's a tiny ghost gang. They're mostly women ghosts. But there's a couple of men in the group too. They're loud, like teenagers, laughing and slapping each other on the back. They say things like, "Is this the place?" "Yeah." "Oh my God this room is ugly as hell." Now our bedroom is not ugly as hell. To give you some idea of how wrong these tiny ghosts are. Our bedroom is actually very nice with flower wallpaper and a matching flower bedspread that I found on sale. Gary loops his arms around my waist tight, like we're about to jump off a plane together. He whispers, "That's the ghost I told you about." Meaning one of the ghosts that just walked in. "Which one?" "The noisy one." Well, they're all noisy at first, so I don't know what he's talking about until the really noisy one speaks up. She talks right to my husband like she knows him. "Hey, Gary," she waves, elbowing one of the ghosts next to her. She has long black hair that's full of waves and little braids. She's wearing jeans and a black leather jacket. "Is this your special lady?" She points to me. Gary squeezes me so tight it hurts. "This is my wife." The noisy ghost laughs. "Then I guess she's the one responsible for this lousy wallpaper." "Lousy," I say, my mouth dropping open. But she's laughing. "Hey, Gary. What's your lady's name?" I answer, not him, because I'm pretty mad at her for insulting my nice bedroom. So I say, "I'm Angie." She loves it. She cracks up at that like, my name is a joke I wouldn't understand. "Classic," she says. "Why?" I say, "What's your name?" And she spreads her arms wide like she's asking for a hug. "I'm Mystika." "Hm!" I say. "Doesn't sound like you're in much of a position to be making fun of names then." Then Mystika does something that really freaks us out. She jumps to the bed. I mean, she jumps, practically flies. Of course I shriek and I climb right over my husband and I duck behind him like he's a shield. Gary's a good man. He holds out an arm to protect me and sticks his chin out. "I didn't know you could do that," I say. "I didn't know she could do that. Listen," Mystika says, stepping closer to us, pointing at us with her arms straight out in front of her. "I own this house now. These are my friends, and I'm in charge. You don't want to mess with me." When she sees that, we're scared, and of course we are, she smiles and flies back to the dresser. And it's so weird when she does it. She stays facing us, flying backwards like she's being sucked back into the door. "Let's get out of here," she says to her friends, and they file out the tiny brown door behind her. Thank you.

[Applause]

[Theme music]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: To read the rest of Amy Giacalone’s story, check the show notes or head to chicagohumanities.org for the link to the book “Ghostly,” as well as the links to the complete YouTube videos of all three of these great programs.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with help from the team over at Chicago Humanities. Shout out to the hardworking staff who are programming these live events and making them sound fantastic. We’re in the midst of our fall season at the moment, and still have a few tickets available to some of our great events. For more than 30 years, Chicago Humanities has created experiences through culture, creativity, and connection. Check out chicagohumanities.org for more information on becoming a member so you’ll be the first to know about upcoming events and other insider perks. We’ll be back in two weeks with a rollickingly fun new episode. But in the meantime, stay huuuuman.

[Theme music]

[Tape cassette click]

SHOW NOTES

CW: Profanity, discussion of taboo topics

Photo: Caitlin Doughty ( L ), Kristen J. Sollée ( center ), and Amy Giacalone ( R )

Watch Caitlin Doughty and Mark Bazer's whole programhere

Caitlin Doughty, Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs? and Other Questions About Dead Bodies

@AskAMortician YouTube channel

Watch Kristen J. Sollée's whole program here

Kristen Sollée, Witches, Sluts, Feminists: Conjuring the Sex Positive

Photo: Victoria Woodhull, "Mrs. Satan" political cartoon

Watch the entire Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark: Audrey Niffenegger program featuring Amy Giacalone here

Audrey Niffenegger, Ghostly

Amy Giacalone website

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- February 20, 2024

Throwing Poems into Lake Michigan with Sandra Cisneros

- Podcast

- March 19, 2024

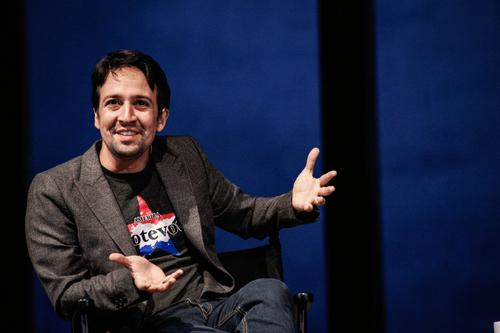

Lin-Manuel Miranda Shares the Secrets to Making Great Art

- Podcast

- November 7, 2023

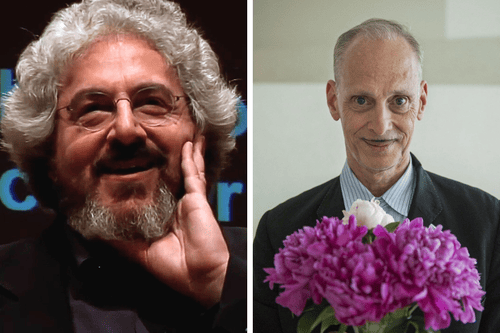

Life Advice from Your Film Dads: Harold Ramis (2009), John Waters (2022)

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!