Rachel Maddow on History, Now, and What’s Next

S3E3: Rachel Maddow on History, Now, and What’s Next

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Hear MSNBC's Rachel Maddow go deep into the rough and inspiring American past in a conversation with Northwestern University’s Professor Kathleen Belew. Topics include Henry Ford, media literacy, and optimism for 2024.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette tape player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Greetings, fellow humans. And thanks for checking out Chicago Humanities Tapes - the spot for the biggest names and brightest minds direct from the Chicago Humanities live spring and fall festivals to your ears. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and today I’m bringing you one of the most impactful conversations from our most recent season. MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, returning to Chicago Humanities to share her thoughtful and informed wisdom on the American history of fascism and what we can do about it.

We’ve got a treasure trove of great speakers coming up in our live Spring 2024 event season - all to help give us perspectives on this election year. Politicos like George Stephanopolous, Joy Reid, Justice Stephen Breyer, plus Kara Swisher on Silicon Valley, Judith Butler on gender, and a preview film screening of the new Netflix film Shirley, starring Regina King as Shirley Chisholm - with so much more to come; it’s such a fantastic season. Tickets go on sale for members March 12th and for the general public March 14th, so head to chicagohumanities.org to sign up for our email list and be the first to know.

Today, #1 New York Times bestselling author and Emmy Award winner Rachel Maddow goes deep into the surprising history of select World War II Americans - some familiar, some that should be - from her fascinating new book PREQUEL: An American Fight Against Fascism, inspired by her #1 Apple podcast Rachel Maddow Presents: Ultra.

She chats with Professor Kathleen Belew, historian and author of such works as Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America.

Please enjoy: Rachel Maddow in conversation with Kathleen Belew, live at the University of Illinois Chicago on October 19th, 2023.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause and cheers]

RACHEL MADDOW: You are very, very kind. And there are so many of you. All right. This is crazy. When I do my TV show, I can't see you. So I'm wearing my reading glasses. So you are blurry, but it's still crazy. All right. I'm really excited about being here. I'm very touched that you're here. I know there's a lot to think about and talk about and want to hear about in the world right now of a book. So it means all the more to me that you're here. I'm also really looking forward to talking to Professor Belew. She is brilliant and she's exactly who I wanted to talk with about this in Chicago. So I'm grate - it's great. I'm going to read a little thing and say a little thing and then I will stop talking. I swear. Do you remember in the. Democratic debate in the first Democratic debate in 2008 when Joe Biden was running for president, when Obama ended up getting the nomination, the first Democratic debate. I remember Brian Williams said to him, "Senator, given what's been described as your uncontrolled verbosity," I remember that phrase, your uncontrolled verbosity, "can you reassure voters that you'll have the discipline you need on the world stage?" I remember that moment. Do you remember what Biden did? He said, "Yes." I'm just trying to take that as my inspiration. Stop talking, you know? All right. He was one of the most successful and celebrated industrialists on the planet. His antisemitism was rank and it was unchecked. He spewed it freely in private tirades among friends, family, close business cohorts, newspaper reporters, or pretty much anybody within earshot, in the office, and private chats in interviews at dinners, even on camping trips. One close friend wrote in his diary after witnessing one late night round the campfire diatribe that Ford, quote, "attributes all evil to Jews."

AUDIENCE MEMBER: (Verbalizing).

RACHEL MADDOW: Good point. Ford even ordered his engineers to forgo the use of any brass in his Model T automobiles, calling brass a "Jew metal." He said, "Wherever there's anything wrong with the country, you'll find the Jews on the job there." He blamed a vast and inchoate Jewish conspiracy for inciting his workers to demand that he share a sliver more of the expensive Ford Motor Company profits. He blamed them for the gold standard. He blamed them for the advent of the Federal Reserve Bank. He blamed them for ruining motion pictures in America. He blamed them for ruining popular music. He literally blamed the Jews for ruining baseball. He was hardly the only radical antisemite in the U.S. circa 1920. But in addition to his fortune and his famous name and his iconic automobile company, he had a megaphone your average crazy uncle theorizer lacked. He had a newspaper. The Dearborn Independent, which she had purchased for a song in 1918, wasn't 44 billion, but it was. Sorry. It's terrible joke. The paper was a big money loser in the beginning, with poor to middling circulation, and Ford's editorial harangues did little to draw new readers. How many attacks on the man who'd beaten Ford in the most recent Michigan Senate race did the public really want? Truman H. Newberry had stolen that election. One of the Independent's editorial staffers, who was a veteran of the New York newspaper wars, had an idea. He wrote to Ford's right hand man, "Find an evil to attack. Let's find some sensationalism." And lo. The answer landed unbidden not long after. A newly translated English language edition titled The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion. The pamphlet was the work of fabulists, Russian fabulists. Furious at the Bolsheviks toppling of the old Czarist aristocracy, the Tsarist portrayed the Russian Revolution as not just a local affair, in their telling it was the early innings of a plot by a cabal of all powerful Jewish schemers to take over the world. The protocols was billed as the product of a surreptitious note taker at a top secret meeting wherein these Jewish puppet masters had drawn up their strategy and tactics. There was no secret meeting, obviously, there was no secret plot. The whole thing was a work of fiction, a considered, very deliberate lie, a very, very dangerous piece of propaganda. Henry Ford seized on it. He and his newspaper bore down on a new weekly series in the Dearborn Independent based on the protocols. It was a weekly series. It ended up being a 92 part weekly series. Every week for 92 weeks. Headlines like these in his paper, "The International Jew: the World's Problem." And "Jewish Jazz: Moron Music Becomes our National Music." And "The Perils of Baseball: Too Much Jew." These were splashed onto the pages of Ford's paper, which is distributed in Ford and Ford Motor dealerships across the country. Ford also cited the publication of his series in book form. It was titled The International Jew, and it ran to four volumes. Never mind that the protocols was exposed as a total make believe right in the middle of Ford's 92 week screed of a newspaper series. Ford's weekly essays continued without pause, and Ford Motor dealers kept tossing the latest issue of the Dearborn Independent onto the front seat of every newly purchased Model T automobile. Ford saw to it that the four volumes of "The International Jew" were translated and published worldwide in 12 international editions, including one in Germany. And stick a pin in that. Of all the contributions Henry Ford made to this world one of them was this: the most prolific, most sustained published attack on Jews the world had ever known. Other Americans organized an anti-antisemitic publicity campaign of notable and notably gentile Americans to stand up against Ford. Prominent public figures such as Woodrow Wilson and Clarence Darrow and W.E.B. Dubois and William Jennings Bryan joined the fight. They called Ford's uttering un-American and un-Christian. The former president, William Howard Taft, soon to be named chief justice of the Supreme Court, accepted a speaking engagement at an Anti-Defamation League meeting in Chicago. Two days before Christmas, 1920. At that speaking engagement, he lambasted Ford and his loony assertions about a Jewish conspiracy stripping power from Christians around the world. Taft said there is not the slightest ground for antisemitism among us. It has no place in free America.

AUDIENCE: [Applause.]

RACHEL MADDOW: Yeah. Go Taft, on that. The German edition of Ford's book landed in the hands of one particularly gifted propagandist. When Adolf Hitler's book "Mein Kampf" was published in 1925, the author appeared to lift not just ideas, but whole passages from Ford's own publications. "Mein Kampf"'s first edition extolled Henry Ford by name. Hitler wrote, "It is Jews who govern the stock exchange forces of the American Union, every year makes them more and more the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of 120 million. Only a single great man, Ford, to their fury, still maintains full independence." Hitler by this point had already mulled sending some German shock troops to America to aid in what he hoped would be Ford's run for president in 1924. When a reporter from the Detroit News showed up at Nazi Party headquarters in Munich in December 1931 to interview Hitler for her series. Her series was called "Five Minutes with Men in Public Eye." She was surprised to find hanging on the wall behind Hitler's desk, a large framed portrait of a famous American. Hitler explained to the newspaper woman, quote, "I regard Henry Ford as my inspiration." The reporter asked Hitler that day point blank why he was antisemitic. He said without hesitation, "Somebody has to be blamed for our troubles." So. The basic idea of democracy just at its fundamental basics, is that everybody gets a say, right? That we all together as citizens, we use the democratic process to elect our leaders, to make manifest our preferences for what our country should do, how it should be run. Right now there are a lot of very smart people who study the rise of authoritarianism and the fall of democracies. Lately, these people are very busy in addition to being very smart. All of those smart people. If you ask them, they'll all have slightly different definitions along these lines what to look for in a country that's at risk of sliding from democracy into authoritarianism. So I just say that as a preface so that you know, that you shouldn't just take my word for it. Lots of - this isn't definitive. Lots of other people who know this stuff better than I do see it different ways. But. My own sort of back of the envelope checklist is that there's four things you have to watch for, sort of four cornerstones. And the first one, I think is the most obvious. It's that the technical, literal part of democracy. Are people able to vote? Do people have their votes cast as they were counted? Do people believe that the Democratic political system is real, that it isn't rigged, that it works? That it is the system we use in our country to effectuate what we want for our country? That's the first cornerstone to assess. The second cornerstone is scapegoating. A disfavored group or a minority being not just attacked, but the subject of conspiracy theories about how they're secretly powerful. They're really to blame for what's wrong in in the country. They're a secret elite that's out to destroy all that's right and good. They're evil. Everybody else needs to be protected for them. You watch for that. You watch for violence entering what should be the political sphere. Paramilitary groups or violent groups associated with certain political factions. Normal political acts like voting or working at a polling place or certifying election results or going to a rally or even talking about politics with your friends or talking about it online. If that makes you subject to physical intimidation or violence, that's bad. And you watch for the disinformation and attacks on the whole idea of truth. And this is one that I know can sound a little woo woo, but I mean it as a sort of basic tactic. If you're telling people not to trust journalism experts in science, telling them that, you know, books are bad and news is fake and history is dangerous. What you're telling people is that nothing is really knowable or true, and so they should therefore go with their gut. Go with your prejudices. Also, maybe just trust what the leader says. And so those if you think about those four things to watch for, if, again, democracy is that everybody gets a say through the democratic political process. Well, why all that? Why are those cornerstones important? Scapegoating seeds in people's minds the idea that we can't let everybody get a say because some people are bad and dangerous and maybe not even fully human, so they can't participate in a mutual democratic process with us. Violence and the threat of violence. Well, that puts the political process off limits to normal people. Devaluing the political process, making democracy not work, or making it seem like it doesn't work. That is, of course, its own reward for people who want us to abandon democracy. And that last point that dislocating people from the truth. That untethers people from reality and knowable facts. And that separates us from our ability to recognize real practical problems and come up with real practical solutions. And that means that we stop caring about government and what it ought to do, and we start becoming susceptible to these useful, distracting conspiracy theories. It softens us up to do what the leader wants instead of what we know is right. So when all those things start getting wiggly, I mean, any one of those starts getting wiggly it's kind of a heads up. When I when all four of them get wiggly, I think it's all hands on deck. And. So that's basically what I want to talk about. I will just say that the the reason the book is called "Prequel" is not because of - it's not because I believe we're dealing with some new iteration of World War Two that, we're not dealing with some new iteration of Hitler or the Nazis today. There's no analogy even between anything in modern history and Germany under the Nazi Party and Hitler from 1933 to 1945, only Hitler is Hitler, only Nazis are Nazis. The book is called "Prequel" not because of the bad guys in it, actually, but because of the good guys. Because from that era, Americans who fought Nazis, Americans who fought Nazi operations that were at work here in America, who fought their fellow Americans who sided with the Nazis, who were working for the Nazi cause, who tried to implement fascism here, who tried to implement an American form of Nazi ism in this country. I believe those Americans gave us a gift. I believe they at least left us stories and lessons for how to think about what your options are when an American ultra right rises. And starts agitating to end our system of government and replace it with a strongman form instead. What to do in particular, what your options are in particular? When a movement like that isn't just on the fringe, it has unnerving connections to elected politicians and people with real political power. We're not the only people in America who's ever who've ever confronted something like this. So. I will just say that, you know, I'm not an activist and I'm not here to tell you to do anything or even to tell you to see anything one particular way. But in 2023 I feel like history has sort of come for us. Um. We are in an era in American politics right now where we we do have stuff that Americans haven't had to contend with for a long time or we've got people subject to physical intimidation and violence. On the edge of politics we've got right wing armed paramilitary groups. We've got that in that denial of election group results. We've got mass disinformation and conspiracy theories and the intimidation of minorities and rising antisemitism. Turns out that's our time. And it has been some other times, too. And it will likely be some other times again. But that means that in the future, somebody will do a book or whatever the future version is of a podcast about our time. About our sort of turn on the chore wheel when this came around for us as Americans who are called upon to save our democracy. And what we do now will be what our descendants and future generations learn about and hopefully learn from, because hopefully we're going to be good at it. So thank you.

AUDIENCE: [Applause.]

RACHEL MADDOW: Kathleen Belew! Yeah!

KATHLEEN BELEW: Hi. So. This is fantastic. If you have not already read it, you are in for a treat. One of the things that I love about this book, as someone who studies the paramilitary ultra right groups that are on the rise now, the landscape of conspiracy theory and disinformation and sort of the I like this chore wheel analogy. I think that makes them like dust or maybe stuff in my garage. I don't know. Um, compost. Um, so one question that came to mind listening to this is because you're in the business of telling stories and directing our attention to things. I would love to hear you talk about why you think as we look back across a century where these groups surge and resurge, where there are always, as you say in the book, extremists out there somewhere, there are always anti-democratic actors. What is it that allows them to evade public opposition? What is it that allows them to resurge? Um, in other words, what is it about the present moment that puts us in this position again?

RACHEL MADDOW: There is something, I think inherent in democracy that if we are in a democratic system agreeing that we're all going to work together to make decisions about what we're going to do as a country, there will be a human impulse in a lot of us, a lot of the time to say, I actually know what we should be doing here. I don't really want this to be a group decision. And that's, you know, that's human. It's okay. But then if you decide to embark on that as a project to get rid of the democratic system, you need to persuade people not only that you ought to be in charge, you ought to persuade people that there's something wrong with the idea that everybody should be in charge, that there's something wrong with the idea that we can all as equals, determine our future together. And so you need I mean, that's part of the reason I read that section of the book. We need somebody to blame for our troubles. And once you blame somebody, pick pick whoever you want to pick, it doesn't necessarily matter. But once you've blamed somebody, that means that we're no longer all the same type of people who are all pulling in the same direction. There are some among us from whom we all the rest of us need to be protected. And then what kind of a system do you have? Well, then you have a system that not only isn't collective decision making. You also need somebody in charge who will use force to protect us all from that evil. And there you go. And so I think the seeds of it are always there, but you need things to fall in place for it to ascend. And. You watch for the technical functioning of the democracy, you watch for the how powerful the movements are to scapegoat minorities. You watch for disinformation dislocating people from the truth. I believe you. I mean, I just think I just think there are structural factors. And then it's worth knowing just as humans, this is we're capable of this.

KATHLEEN BELEW: One of the things that's stunning about the book is that you take a number of events that people might have learned something about in their history education, I hope. And reveal that a lot of these are interconnected. So we see America first. Militias connected to, Huey Long's electoral machine connected to Charlie Coughlin's radio sermons, connected to sitting lawmakers who are in the business of attempting to undermine American democracy and even to align the country with Nazi Germany. Those network connections I find really interesting, and it all builds to a question that we are always asking, I think, when we are dealing with anti-democratic movements. But to what extent can the court system effectively respond? And I'm thinking of the recent string of sedition conspiracy, seditious conspiracy convictions for people in the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, particularly coming out of January 6th and the run on the Capitol. There are other examples in the '80s that we can talk about if people ever want to. But the centerpiece of this book is the Great Sedition Trial of 1944, which is huge and just utter chaos. So I'd like to invite you to cue that up for the people who have not yet read the book. And then I have subquestions.

RACHEL MADDOW: Well, yeah, it's very hard to convict somebody in the United States of seditious conspiracy. We have the right to not just think terrible things. We have the right to associate with other people for terrible reasons. I mean, we have a lot of rights protected under the Constitution, and God bless us for it. But it means that a lot of political organization, even of the most sort of nefarious kind, is protected right up until the point where you take action to use force to undermine the government of the United States. But if you think about it. If you are in the position of being put on trial for sedition, that means your effort to overthrow the government by force did not work because there is a government still standing to put you on trial for sedition and so on. And so almost inherently, the prosecution has an impossible task of convincing a jury or convincing a judge in a bench trial that this plot was a real threat and is worth testing the boundaries of our constitutional protections for speech and association and political activity, because obviously it didn't work. So maybe it was never going to work. And that is what you run up against. That's part of why this the Great Sedition Trial was forgotten. I think it's part of why the the whole movement around them was forgotten is because it was in their interests at the time to say, oh, we didn't mean it. It was it was it wasn't ever going to be a threat. And I think a lot of observers can sort of dismiss it that way. When the Christian Front Militia, Father Coughlin's militia, was put on trial in New York in in 1940, the FBI raid on the Christian Front Militia, they thought they believed was less than a week out from when the Christian Front was going to start its plan for violent overthrow of the U.S. government that was going to start with the murder of 12 members of Congress. They thought they were a week out from that. And the Christian Front guys all got off. And their defense was effectively, aw? These guys? Were going to do something like that? Come on. They had stockpiled bombs. They had stolen U.S. military machine guns. They had lots of members of the National Guard and the New York Police Department who were on their side. They had a lot of money and they had direct support from Nazi Germany. So in the moment and looking back at it, it's you can say, oh, these were a bunch of clowns. But. I don't think they were.

KATHLEEN BELEW: That trope of these were a bunch of clowns. The coup could never have happened. It couldn't have happened. Like, it's not really a threat comes up over and over and over again, as do all of these other factors except the part with direct support from Nazi Germany, which is, of course, not a thing after this book, but in the 1980s, we're looking at the same set of things organized paramilitaries with some amount of buy in from official people were looking at stolen weapons from armories and posts. We're looking at military grade stuff, we're looking at readiness. And again, it's that same tactic of saying it could never have happened. These guys are a bunch of loony. They describe one of them as the Bayou of Pigs. By way of making fun of it, they describe others as being, you know, various kinds of redneck hijinx.

RACHEL MADDOW: The Christian Front - they were the Brooklyn boys. Yeah. Oh, sweet. Yeah. And their machine guns and their stockpiled bombs.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Exactly.

RACHEL MADDOW: The Brooklyn Boys.

KATHLEEN BELEW: And it occurred to me reading this book, so. Mild spoiler. The Sedition Trial in 1944 is a really big mess like.

RACHEL MADDOW: 29 defendants and 26 defense counsels, plus a lot of marshals, plus a lot of prosecutors, plus a lot of reporters all in the same courtroom. Free air conditioning. And it went on. It was bedlam. And it went on for seven months. And then the judge died. It was and he and the prosecution hadn't even gotten 30% of the way through their witness list at that point. The prosecution had a pretty compelling case, but they got nowhere near being able to put it together.

KATHLEEN BELEW: They can't even make the opening statement, right?

RACHEL MADDOW: The opening statement takes an entire day and nobody hears a word of it.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Because people are just shouting over the prosecution.

RACHEL MADDOW: They're chanting and screaming together. It's amazing.

KATHLEEN BELEW: And then there is people like leaving court to go lead antisemitic songs somewhere else or like showing up on the steps, wearing just a nightgown and doing all kinds of hijinx that just distract from the trial. It made me think about the Charlottesville case, which is a civil trial, of course. This is the case coming out of the Unite the Right rally in 2017. But it made me wonder about to what extent do you think a whole bunch of defendants choosing to represent themselves makes them look disorganized? Is that a tactic instead of a feature?

RACHEL MADDOW: Yes. If you maintain a professional, organized, dignified defense, you kind of seem like a professional, organized, dignified person whose actions and words ought to be taken seriously. But if you behave like the pro se defendants did, the defendants who defended themselves in the Charlottesville civil case or you or you behave like some of my defendants did in this case, literally showing up in a nightgown and one guy standing up in the middle of the trial and saying "I demand a mental exam!" And he meant for himself. I mean, this is there's this is it's hilarious. And it just and I have an eight year old sense of humor. And so I find all of this hilarious and definitely entertaining, but it also is strategic. And there's also just a technical nuts and bolts about it. I was very interested in the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys seditious conspiracy trials that we've had in the last few months that even though they indicted about as many pro-Trump, right wing armed paramilitary militia members in the post January 6th trials, there was about as many of them as there were my guys in 1944. They did not make the mistake this time of putting them all on trial at once. They broke them down into groups of of four and five. And just that, just learning that. Okay, take take that lesson to the bank as well. It's it is hard to prosecute people for crimes that have political intentions. But crimes are crimes and violence is violence. And the Justice Department has to be a role. It can't be the only thing we do. It almost never works on its own. But you can't abandon it either. At least that's what I think this era was trying to teach us.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yeah. So relatedly, what role do you think the news media plays in this story and also today in shaping how we think about and have conversations about anti-democratic movements and threats?

RACHEL MADDOW: Well, I mean, I hope we're getting better at it. There are among the heroes in prequel a number of journalists. So part of when I say, the Justice Department has to be part of it, but it can't be all of it. One of the most effective forms of activism, and it's not even activism. So it's sort of pro-Democratic practice that I think, it's helpful, at least to me, to study and to learn from it and to know that people did it before us is just documenting what these groups are doing. So it's controversial investigative columnists like Drew Pearson, who everybody hated, everybody on all sides of the aisle hated, everybody talked to him, but nobody trusted him. He was he was more controversial than any mainstream journalist today and more influential, I would say. But he had sources in the Justice Department that told him that Senator Ernest Lundeen recently died in a mysterious plane crash. And the subject of all of these strangely lukewarm endorsements and eulogies from his colleagues was at the time of his death, under investigation by the Justice Department for working with a Nazi agent. Drew Pearson blows that open. Dillard Stokes blows open a different part of it involving the America First Committee in in Washington, including spy movie-style stakeouts of of of evidence that's transiting the city in the dark of night. And there's there's journalists who do great work. There's also American citizens who do effectively journalistic work researching, investigating, in some cases infiltrating these groups and then writing up their findings and telling law enforcement and telling the public. That's very dangerous work, but exposing the nature of what these groups are doing. And they do all try to stay some level of secret has the benefit of exposing the American people to the truth of it. And then the American people can make their decisions about whether or not these guys' arguments are going to be compelling. You can see what they're trying to do with their arguments. And you can judge for yourself, these members of Congress who seem to be defending them, siding with them or even working with them. And that allows you to vote those people out. And so having information, real, knowable, checkable information is indispensable.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yes. What do you, I want to talk about, O. John Rogge. And I'm looking for my in. But he's the major character in the story, partly because of the Great Sedition Trial, but also in his dealings with Huey Long's Louisiana. So I wonder if we want to start Rogge in Louisiana and then follow him a little.

RACHEL MADDOW: So Huey Long, I feel like, is due for a historical moment in pop culture. I feel like we're ready to learn a lot more about what Huey Long was like, in his time, both in court proceedings and in newspaper accounts and even like in the titles of books about him. Everybody just matter of factly described him as America's most likely candidate to be our Hitler. He was routinely described as running a dictatorship in Louisiana. He was governor of Louisiana, and then he got elected U.S. senator from Louisiana. But while he was U.S. senator, he decided he'd stay as governor. There's your sense here. I mean, it didn't last forever, but for a long time he was both. After he was no longer governor, he had built a gigantic skyscraper state capital in Louisiana that had an apartment for himself at the very top of the tower. And after he was no longer governor of Louisiana, he kept the apartment. He also once mounted an armed invasion of New Orleans. And just got away with it. Huey Long was amazing. He was the person who Franklin Delano Roosevelt most worried would run for president against him in 1936. And Huey Long's politics are, for me, of less interest than his tactics. A lot of people identify him as a figure of the left. I think there's a great argument to be made for that. He certainly was a populist. He was also an unreconstructed demagogue. And profoundly, profoundly, profoundly corrupt. And the Justice Department, after Huey Long was assassinated in 1935, realized that the Long machine in Louisiana was so well put together that even the death of Huey Long had not taken it apart. And so they sent this young whippersnapper prosecutor down to Louisiana after the death of Huey Long to go break up his machine, to go return Louisiana to democracy. And this young prosecutor went down there. He said he thought he'd be there for a few days and he was there for months. And there's a scene that you might remember from the Ultra podcast if you listen to it, where he gets a letter at his hotel room where he's staying. That includes both a death threat and a bullet. And he receives that and he walks straight out onto the street in the middle of the night. And calls a press conference in the middle of the night and says, effectively, you can't stop me. We won't be intimidated. And if you get me, there'll just be another prosecutor behind me. Give it up. And he breaks up the Huey Long machine and he puts the governor in prison and he puts the it breaks the machine up, and it's this. It is a it's a career making thing for this young prosecutor. And the next thing they have him do is go prosecute the Christian Front, the Brooklyn Boys in 1940 and he blows it and he does not recognize how positively inclined the Brooklyn jury pool is toward these Christian fascist militiamen who have been stockpiling bombs and planning to kill a dozen members of Congress. He so is so blind to the local support for these guys that he neglects to discern during jury selection that the forewoman of the jury is not only the first cousin of the Christian Front's priest and leader, but she is related as well by marriage to the Christian Front's lead defense counsel. And John Rogge misses this. And the Christian Front guys walk. And then when political pressure is brought to bear on the attorney general of the United States and the investigator, the prosecutor who's leading the investigation of a nationwide sedition trial is fired from his position because he's getting too close to members of Congress who are implicated in that plot. They bring in John Rogge to clean up. And run the prosecution instead. And he does. An amazing thing for this country, and it is work that I believe stands up 80 years later. But he doesn't put any of those people in jail.

KATHLEEN BELEW: He does write a report, though, which we get much later.

RACHEL MADDOW: Yeah.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Tell about the report and why nobody reads it.

RACHEL MADDOW: So.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Small spoilers.

RACHEL MADDOW: After the judge dies in 1946, important, it's '46. So World War Two is over. That means that John Rogge while the just what happens when the judge dies is that the defendants at least in this case, were offered the chance to just pick up where the trial left off with a new judge, which of course, they said no to. And then it's going to it's a mistrial is declared. And the Justice Department has to decide whether they're going to start all over again with this trial, with the 29 defendants and the 26 defense attorneys and the dead judge and the 30%. I mean, it's are they going to do it again? While they're mulling this possibility, John Rogge says, please, boss, can I go to Germany? Because what we have alleged here is that these people want to commit sedition. They want to overthrow the U.S. government by force, but they are doing so in a conspiracy with the Nazi government in Berlin. That America's purportedly homegrown fascists also have foreign ties to the enemy that we just beat in this war. Can I go check with the enemy that we just beat in this war and find out if it's for sure true from their side too? And he goes to Germany and he interviews Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg. And he goes through the German government's files. And he, sure enough, documents all the ties between America's fascist movements of the time and Hitler's government. And he brings this information back to Washington. And he has made an arrangement with the attorney general that whether or not the trial is going to be pursued, this information will be laid before the American people in a public facing report. And that is the operative assumption that he brought to Germany with him and that he brought home when he wrote up his report. But the attorney general takes one look at it and sees the names of two dozen members of Congress there. Including President Truman's best friend. And he takes it to President Truman and he says effectively. The two of them make a decision and they decide this report will never be released to the American people. And this will be put in a desk and it will be this is this is it. And Rogge is fired. And he goes on a speaking tour to tell the country, to tell everybody what's happened. And he, very briefly, is a national hero. And then everybody moves on. The war is over and he fights for 15 years to have that report published. And it is finally published in 1961. And boy, has the country moved on by then. Nobody reads it. Nobody reviews it. Nobody. It doesn't sell. Part of the reason it's so hard to get now is they printed so few copies of it because there was no demand for it. And yet, that that report, which did not pay off in his lifetime, I believe is an indelible and I believe invaluable history lesson and instruction book for us in terms of what it means as Americans to face up against a movement that is that anti-democratic, that powerful, that connected, that wily and that resistant to control by the criminal justice system.

KATHLEEN BELEW: So there's a great AUDIENCE question from Dr. Marilyn Stocker, who would like to know: with all that you know and see going on in our world, are you hopeful? And if so, what is that optimism based on?

RACHEL MADDOW: Are you hopeful, and if so, why? There's this thing that Susan, my partner, Susan, and I say to each other, which is "sometimes the answer is in the question." And I guess I know what our AUDIENCE MEMBER believes about whether or not we ought to be hopeful. Yeah. You know, listen, I, I started working on this because I felt like I needed help from history to know the origin story of some of the ugly things that I feel like are coming back around that I didn't expect to be coming back around. And learning the origin of these things helps me understand them myself and helps me explain them to other people. And I see that as my job. So that's why I was looking into it and trying to learn it. The reason I decided to make a podcast about the trial and this book about other parts of it is because I do think history helps us not just explain precedent. I do think it gives us a sense of what the options are for how we can act. I mean, again, there's no there's no new Nazis, right? There's no new Hitler. There's no there's nothing that's not that's not the lesson here. It's not to find in today's authoritarian movements, echoes of previous authoritarian movements. Authoritarianism and fascism is always the same. Shirtless guy. Don't trust the Jews. We can't have democracy. Like, don't go to the rally, people will beat you up. Like it's all this the same thing. It's an all it's all in all countries. It always kind of looks the same and I'm being reductive, but it's basically true. What is different all the time are the resources that are brought to bear to embarrass, discredit, oppose and beat back those movements. There have been fascist movements all over the world and in our own history, and there's all of these forgotten Americans and forgotten anti-fascists everywhere, all over the world and in our own history who had great ideas and did things that were hilarious and effective and surprising. And very few of them were even thanked for it in their own lifetimes. But we don't have to be constrained by that. We can go back and find what they did in their lifetimes that's helpful to us. That's interesting to us. That gives us new ideas about what to do today. Um, and so I just, I do, I do feel hopeful. I feel like there's endless depths of stuff to plum here. And if, if, if we were up against a movement in the lead up to World War Two, an anti-democratic, antisemitic, pro-fascist pro-Nazi movement that had effectively on its side the most famous industrialist in the country, Henry Ford, the consensus national hero of America, the most famous man in the country who was not the president, Charles Lindbergh, and the most influential media figure who has ever existed in this country since the beginning of this country, Charles Coughlin, all on their side and the largest voluntary political organization in the country and growing by leaps and bounds at the time. If all of those forces were arrayed on that side of the equation while Germany was steamrolling through Europe. And those people lost here. Well, we can beat the pikers that we're up against now. Right. I mean.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Well said. We historians have a word for one of these things, we talk about contingency, which is the idea that events are not predetermined. So if you're in Germany in 1933, we know from here the string of events that's going to happen. But people then didn't know that string of events. People didn't know when they're stepping up to confront this threat that America was going to win the war, that this was going to get resolved, that things were going to work out for them, that these forces would have to go back underground in some cases. There's this sense of contingency. And I think that that amplifies many of the acts of sort of real world heroics that appear in this book. So I would like to, before we move on, invite you to talk about that, we can't do all of them, but there are a few characters in here that maybe deserve a highlight. I like the secretary.

RACHEL MADDOW: Oh, the secretary. Yeah.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yeah.

RACHEL MADDOW: Yeah. You know, there's the contingency part. I was. Let me just say on that point, one of the things I was thinking about today, getting ready to come over here was that when you read like the America First Committee speeches, one of the points that they make that is most compelling even now, even knowing how it turned out, is when they're arguing about how if we join the war, we will lose. I mean, they're arguing against the United States joining the war in Europe, in part because Hitler has taken everybody except England. And why do we think we're going to be able to turn that back around? It's actually one of the strongest, most rational arguments that they make. And, of course, we know from history that that's not at all how it turns out. But it's to me, looking at the primary source stuff, looking at the text of what they were doing rather than just people later writing about it. It's a good reminder. When Gerald Nye, who's one of the senators who's involved in all this stuff. On the day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Gerald Nye was leading an America First rally and somebody brought up a piece of paper to him on the stage and told him Pearl Harbor has been attacked by the Japanese. And he just kept going with his rally. He just put the piece of paper down and kept going, arguing about how we would lose and we will never be attacked. And we are protected by our oceans. And this isn't our war. And why the war is lost anyway. And why are we going to plight our trough with all these defeated empires and ultimately people, Americans in uniform, I don't know whether they were active duty or what was going on, but soldiers ran in and tried to stop the rally to say, we are at war now. You need to like you need to know this is happening. And he all but fought with them, not wanting to tell his AUDIENCE that the Pearl Harbor attack had happened because he said he could not believe it, because I believe he couldn't believe it. I believe he had talked himself to the idea that we would never be attacked and that we would ultimately end up needing to side with Germany. We should do so as early as possible to cut the best deal for when Hitler invaded us. And. It's just it was very present and very real. And to me, that is also heartening, as you say, because it does heighten the heroism of the people who had clarity of purpose even against that kind of uncertainty.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Absolutely. I think history has a lot of lessons for us, not only about where we are and how we got here, but also the many roads not taken, the near misses, the possibilities. And sometimes it can be an engine for kind of widening our realm of thinking about what's possible.

RACHEL MADDOW: Yes. Yes. And then just the idea that nothing is inevitable, everything looks inevitable in retrospect. Nothing's inevitable in the moment. That's connect it to the secretary itself, just thinking about human level heroism and people who did a solid for their country, even though they woke up that morning not knowing they were going to be called upon for it. One of the people who I think is it's worth spotlighting is somebody who worked in the office, was a secretary for Senator Ernest Lundeen and the guy who died in the plane crash. Senator Ernest Lundeen. He may have had a lot of nice things about him. I didn't find any. One of the things that was not nice about him was that he stole from his staff so his congressional staff would get paid every week and then he would demand from them a cash kickback in their salary and would pocket it. And if you wanted to work for Senator Lundeen and this was part of the price of admission and so one of his secretaries who was in a weak enough position at work that this was her job, that she was handing over a piece of her salary every week in cash to her boss. So it's not like she was in an empowered position at work. Nevertheless, after he was killed in this plane crash, his wife scurried across the country as fast as you could get, as fast, fast as you could go. And this wasn't at a time when air travel was easy to align and on short notice. But she she got, her husband died in a plane crash. And within two days, she had gotten herself from Minnesota to Washington, D.C. in a hurry. And all she wanted from his office was one file, of correspondence with one guy which she took away. And Senator Lundeen's secretary had the presence of mind to recognize what this was about. And she went to the FBI and said, "The correspondence that you're looking for of my boss with that guy who you're now putting on trial is a Nazi agent. His wife has it." And that's I mean, you never know when history he's going to come knocking. Right. When heroism is going to ask if you're home. Um, but it's it's not it's not just people who join the Marines, right? It's it's Americans getting called upon in all sorts of ways to save their country.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Nancy would like to know what is the United States of America fighting for in the 2024 election?

RACHEL MADDOW: What is the United States of America fighting for in the 2024 election? I, I think this is going to be a very difficult year. And, in some way, if you were just writing a novel about your time on Earth, maybe this would be a great time for the drama of of life. Because it is I think not hard to have moral and even strategic clarity about what are the stakes for us in this country over this next year heading toward the 2024 election? I think that it is not hard to see around the corner to know that we want this not to be the last election, that we want to hold on to democracy the way we do things in this country. But it's not just drama. Right. And it is something that we're living through. And the result is not inevitable. And things can go bad and things can go surprisingly bad and things can go bad quickly. And at a time when there is this much precarity in our democratic project. I do think it's an all hands on deck moment and not everybody needs to do the same kind of work, but everybody does need to do something. Even if you don't, you imagine yourself having a determinative effect. You might be the secretary. You never know when you're going to be called upon. Um. And I will also say that part of standing up for democracy means making democracy work. And so democracy isn't a concept. It isn't something that exists as the negative form of fascism. Democracy is a decision process that we use as citizens to make manifest what we want for our country. And so if you are standing up for democracy, that means you believe in democracy. And that means in this year, I mean, I believe it means you put aside whatever cynicism you might have previously earned in life about whether or not democracy is awesome. Right now, we're it's we're in the position of missing it when it's gone. And so, yes, it needs to be fixed and improved, but that's what it means to use democracy. So whether or not you were planning on being a poll worker this year, think about it. Whether or not you were thinking about working on a campaign. Think about it. Whether or not you were thinking about doing souls to the polls. Think about it. Whether or not you were thinking about doing anything in your local community to make sure democracy just works. You're doing something for your country at a time your country needs you.

KATHLEEN BELEW: So speaking of everyday heroes, we have a question from Tara Tate, who you're going to want to clap for in a minute that says, I am a high school government teacher and I include media literacy in my curriculum.

RACHEL MADDOW: Oh, God bless you.

KATHLEEN BELEW: What is the one piece of advice you would give young adults in how to process information from all of the different outlets they are exposed to?

RACHEL MADDOW: Oh, this is a great question and an inspiring questioner. So thank you. I listen, it's actually it's not a very inspiring answer. I think it's very nuts and bolts. But I actually think that learning what journalism is is a helpful thing. So there's lots of different ways that people can get information and circulate information. And social media has made it a much more iterative process than it ever was before, you know, back and forth between people. And that's good. And that's that's democratic in its own way. But learning the difference between information and journalism, I think, is helpful. Just so you know, if you do want to assess the veracity, the trustworthiness, the validity of something that you want to cite or share with somebody else, you have some tools to do that. And so learning about sourcing. What is the source of this information? Is the source named? Are there multiple sources? Are the sources that are named in this piece of reporting or this piece of information, sources that are the type of source that should know the truth of this thing that is being attested to in this reporting? And what is the entity that is standing behind this reporting? Is it a news organization? Is it a news organization that you know anything about? Is it a person who you have reason to trust or distrust? And is there anything that you can do to see any of the raw material that they used to put this piece of information together? If they're talking about something that happened in a courtroom, there should be a link to a court document. You don't have to read the whole court document, but you might want to look and see if it's there. If it's something that's being described for which there were news photographers or even civilian photographers there. Are there timestamps on the photos that purport to be of the thing that you're describing as having happened in a time sensitive way? Just learning about what that is. Learning that in a in a news organization, you not only need to define your sources, your sources need to meet certain standards, and then you need to answer to an editor who is responsible for the professional standards of that news organization. And you can judge news organizations by their standards. Know, just knowing that having that be a basic part of your alphabet that you use when you read the news can help cut out a lot of the dross, I think. And it gets worse all the time in terms of the way information circulates online. But for me, working for NBC and MSNBC, it's it makes me feel all the more grateful to have the job that I do and that we have big, reputable news organizations who don't always get everything right, but who at least have standards, have professional tactics and who correct things when we get them wrong. I will also just say my boss is here tonight. His name is Corey and it's his birthday. And he'll like that answer. So happy birthday, Corey.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Happy birthday Corey. Relatedly, we have a question from Frank Kress, who asks: in a world where we were all in our own bubbles regarding sources of information, how do you recommend trying to see issues from other people's perspective? So this goes to polarization and the way that we consume totally different news sources. Um, and also the way that we have very different ideas I think now about what is evidence, what is an argument, what is a fact?

RACHEL MADDOW: Yeah. I mean, part of it is making sure that you're consuming quality information and paying attention to sourcing. Looking at who's the author of the information that you're getting. That's that's part of it. But I also think just it's a good rule for journalism. It's it's a good rule for life to just read widely. Don't let the short attention span sort of way that we live now constrain your ability to read book length ideas. And if you're not up to reading a book length idea, how about a magazine article instead of a newspaper article? And if a magazine article feels like that's too expensive or too much, how about a long newspaper article instead of a short one? I mean, honestly, it helps. Part of the reason that I changed my work schedule at MSNBC is I felt like I was thinking shorter thoughts and I was reading shorter pieces of information. And I wanted different deadlines that arrived at different times on different horizons so that my brain could flex a little bit. I recommend reading widely and reading not necessarily on things that you are already convinced you're interested in, but something that maybe grazes it. I would also say just at a human level, and I think this is an important small d democracy thing that we can all do is just to make sure that you have personal relationships where you talk with people about maybe current events and maybe the news, but maybe not. Having relationships with people who are different than you, who are coming from different places than you were. Maybe you're not talking about Donald Trump and maybe you're not talking about Joe Biden. Maybe you're not talking about the election. Maybe you're talking about the Cubs still having a, oh.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Or the White Sox.

RACHEL MADDOW: We're going - maybe you're talking about the 40 Niners.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: (Verbalizing)

RACHEL MADDOW: Maybe you're talking about the weather. Maybe you're talking about music, maybe you're talking about other things, having personal relationships not mediated through your phone. Or if they are mediated through your phone at least they're with individual human beings with whom you text or talk. Having human connection to other people makes you see things through other people's eyes. And not everybody in your circle of friends will see things the same way you do. Even if you're all liberals or you're all conservatives. You'll have different family backgrounds, you'll have different backgrounds in terms of immigration and work and family life and taking care of elderly parents and taking care of kids and having a multiplicity of human appreciation in your life and not living in your phone, not just living online makes you a more empathetic person and helps you see things through other people's eyes. And that is sometimes in extremis, that's what things come down to. Um, but it's also, it's a, I think it's a recipe for a healthier life. And I think it's a recipe for a healthier democracy.

KATHLEEN BELEW: I think community formation and neighborhood ties, interpersonal ties is also a really important tool for any kind of organizing, but especially for organizing against intimidation and scapegoating and the sorts of what did you call it, the four corners of the envelope.

RACHEL MADDOW: Four cornerstones.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yeah, the four cornerstones. So the cornerstone to do with scapegoating and the rise of paramilitary groups, community wellness and community organizing in the sense of just knowing your neighbors, making sure people are okay is one of the single things everybody can do quickly. So that's a.

RACHEL MADDOW: Really important point because when you say community organizing, people think organizing toward a political end.

KATHLEEN BELEW: No.

RACHEL MADDOW: And that's true, too.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Sure.

RACHEL MADDOW: But this is about resilience.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yeah.

RACHEL MADDOW: Just knowing your neighbors, whether or not you like your neighbor, just knowing your neighbors is helpful if something comes down in your neighborhood.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Yeah.

RACHEL MADDOW: Knowing people enough to say hello can be an important thing when something befalls you together.

KATHLEEN BELEW: And Chicagoans know this lesson really well from everything from, you know, shoveling and putting the chairs in the spot, which is a highly contentious local issue to things like how do you actually get a tree removed when it falls on your block? We know about this, right? So this is a an application of a Chicago skill set.

RACHEL MADDOW: I would also say that, you know, people talk about urban and rural divides in terms of what Americans think about the Democratic project. And I live in rural America where I feel very I live in rural western Massachusetts. I feel very interdependent in my neighborhood and in my community because we have 14ft of snow a year and we have all sorts of crazy things that happen to us and we have bears and we know like stuff happens and you need to know who you are and you can't be like "that guy who watches 'Hannity' and so I am not letting him dig out my fire hydrant." Like, you know, who cares? Who cares? And there's this idea that, like in rural America we're conservative and we care about each other and in urban America, we're liberal and we don't care about each other. And I just feel like it's completely, totally untrue that it's not one thing or the other. It's glad that we have interdependence and community strength of all different kinds in urban and rural areas. And it's I think it's worth if you don't have enough of that in your life, don't see that as the truth for now to the end of your life. That is something that you can work on too. And if you don't have enough other people in your life who you see regularly, ask. Do stuff with other people that you might have to ask to do. Tell somebody "I'm looking to make friends. I would like to talk, do a book club with you guys. I would like us to get together in person rather than only seeing each other at Thanksgiving." You can you can make change along these lines, and you never know when it might save your life.

KATHLEEN BELEW: Not sure we can follow that, but I'll try. Oh, here's okay. Lisa Martin would like to know: looking at all of the events that have unfolded over the last several years, and I I'm just going to assume that we all know what they all are. But, I mean, we could pick any. But she would like to know what has shocked you the most and why. In other words, is there a development in American politics or American life that really took you off guard?

RACHEL MADDOW: Hmm. Um. I don't know. I'm pretty. I think I'm pretty humble about knowing that my crystal ball doesn't work. I mean, I guess I like reporting on politics and stuff like that. I'm the world's worst predictor. I get stuff wrong all the time. But I also don't believe in my predictions in the sense that I don't put much stock in them. I know I'm always wrong. So I don't get shocked when something that I expected to happen doesn't happen. I think I will go back to something that we said at the beginning here. Part of the reason that I started working in in this in this area of research, in this part of history was because something came around in U.S. politics that I didn't expect to see anywhere other than that the deep fringe. And that was the resurgence of Holocaust denial as something quite close to American mainstream politics. And Holocaust denial, among other things, is insane. It's it's it's terrible. And it has, it functions. It has a million horrible functions in the world and is morally odious. But it's also just weird. The Holocaust was not that long ago. There are Holocaust survivors among us. There are there are American GIs who were not Holocaust survivors themselves, but were eyewitnesses to it who are among us. This is something that we started contending with, people denying this reality as early as as far as I can tell, as early as 1948. When there were so many people around who had lived through it and in many cases just barely. So how is it that that's back around? How is it that we've got groups with swastikas on the overpass of the 405 in Los Angeles or outside Disneyland with swastikas in one hand and Ron DeSantis flags in the other. How is it that we've got I mean, actually in western Massachusetts in rural western Massachusetts, where I live right now, there's an article in the local paper right now about a local Nazi group putting antisemitic pro-Nazi fliers on people's front steps and car windshields. But why was this stuff coming around again? It's part of the reason that I wanted to do this work, because I did I do find it just not just bad, but weird and starting to look into the origins of it in the United States brought me back to to brass tacks. Which is that that kind of stuff exists not because somebody's been mesmerized into believing it. That kind of stuff exists and is not just a privately held belief among people, but something that they are propounding in the country for a reason because they want to advance an anti-democratic project that is that depends on scapegoating, that depends on the antisemitism that excuses what we associate with authoritarianism, fascism and naziism. And they need Holocaust denial to be able to do that. And so once you start to see it as a thing that's being done for a reason, I think it makes it a little bit less scary. It's still just as disgusting and angering, but it's not as scary because you can see that people are doing it for a reason. And once I understand somebody's motives, I'm less subject to the power of their words. Once you tell people, hey, this is being given to you, this being shoveled to you to manipulate you. If people can understand that, they're less manipulable. When faced with that again. And that's valuable, I think.

KATHLEEN BELEW: So thinking about wrapping this up, I wonder if there is a lesson that you would like to draw from the process of looking to history to understand the present. In other words. Would you like us after reading this excellent book, which we're all going to do, would you like us to go out and read additional history? Are there ways that you would like us to approach the world with that set of curiosities? Or is it sort of a mindset of looking for that kind of loose thread on the sweater and then not letting go that we can take with us out into the world?

RACHEL MADDOW: Well, obviously, everybody should be a history major. You have to say that in front of your interlocutor, the history professor. Listen, I think that everybody's brain works differently. My brain works in such a way that I cannot um I was telling Kathleen earlier today, like Susan said, like, "Didn't you have a story to tell me about something that happened? You said something weird happened in the parking lot at the Stop and Shop when you had to do the grocery shopping." I'd be like, "Yes, I've been. Oh, thank you for reminding me. Okay. First the dinosaurs were destroyed by a meteor. And then as the Earth went through one of its early ice ages" and she's like, "Cut to the chase." Like my brain, I get rightfully dinged for always going back to the prehistory of the prehistory, of the prehistory of the great, great, great, great grandmother of the story. But I. Corey, I'm sorry. And you, you know, you either like that or you don't. But that's the way my brain works. And so for me, I need to know the origin story of the people that I'm talking about or the movements that I'm talking about or the moments that I'm talking about. And so for me, I need to I don't need to I don't always need to go back to the meteor, but I need to go back pretty far until I'm I'm confident that I have some sense of where this came from, how how else it might have gone if it hadn't gone the way that we're talking about. And so maybe your brain works that way, too. If it does, I would tell you, don't be afraid. History is there to help, look stuff up. If you get to a part if you're reading something that is starting to make something some sense and then you get to a part that doesn't make sense, then look up that thing. The the access that we have to information right now makes this a fun way to spend time. Um, but I would also say that maybe history isn't your jam. Um. If that's not the way you learn. One of the other things I would encourage you to do is, as I said earlier, read widely read stuff that is longer than you are typically comfortable reading. Read, if you if you find somebody who's written a magazine article or written like a news analysis piece that you find valuable, go figure out what else they've written. Read those things, too. There is a way that I think you can kind of widen your intellectual stance and get there and therefore get more stable by just doing more to understand the world around us. And in the weird year that we're about to have and in the incredibly high stakes election that we're about to try to have. Um, I think that the more connected we are to our families and our communities and to the intellectual tradition of this country, that is why we have the system of government that we do, the more resources we're all going to be able to bring to bear to doing something to help, because this is going to be a year when your country needs your help. Kathleen, thank you so much. This has been amazing. And thank you all very much for coming. Thank you.

[Audience applause and cheers]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Rachel Maddow with Kathleen Belew, live at the Chicago Humanities fall festival on October 19th, 2023.

For links to all of the works mentioned, scroll down to the show notes or head to chicagohumanities.org/explore/podcast for all that good stuff and more.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with assistance from the hardworking team over at Chicago Humanities who are producing these live events and making them sound amazing. We’ll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode for you. But in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays out]

[Cassette tape player clicks closed]

SHOW NOTES

Rachel Maddow ( L ) and Kathleen Belew ( R ) on stage at Northwestern University at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in October 2023.

Rachel Maddow, Prequel: An American Fight Against Facism

Kathleen Belew, Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- April 18, 2023

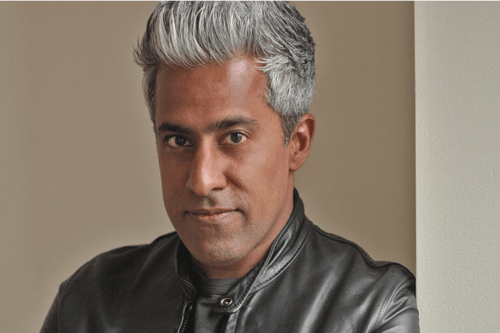

Is the Public Still Persuadable? with Anand Giridharadas

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

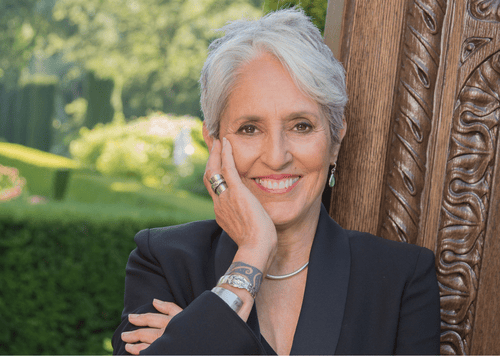

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

- Podcast

- September 26, 2023

Patti Smith Reflects and Lives in the Moment

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!