Mini Tapes: The Subversive Act of Math

S3E8: Eugenia Cheng

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Overcast • Pocket Casts

This one's for the math nerds, teachers, and forever students. Mathematician Eugenia Cheng, the Scientist in Residence at the Art Institute of Chicago, explores the surprising way that the logical quality of math is revolutionary in a time when humans can struggle to understand other perspectives in this conversation with Golden Apple award-winner Luke Albrecht from 2017.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey guys what’s going on. You’re listening to Chicago Humanities Tapes - we are the audio extension of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and this is Mini Tapes: one great story from one great program. Today: Mathematician Eugenia Cheng, the Scientist in Residence at the Art Institute of Chicago, chatting with Golden Apple award-winner Luke Albrecht, about how the subversive little act of doing math, in broad daylight, is in fact revolutionary. This conversation was recorded live at Chicago Humanities at the historic Fine Arts Building in spring 2017.

[Theme music plays]

LUKE ALBRECHT: I was talking to my son or actually my son started talking to me this week. We were sitting on the couch. He's eight, and he turned to me and said, If I'm counting, there'll always be another number. And does that mean that I can name the next number as we go towards infinity? Is it possible that he can name the next number?

EUGENIA CHENG: Anything is possible, almost. And the fact that small children can get excited about it is great because it means that they feel something about math. And unfortunately, many people only feel fear and hatred about math. And and although that is something to feel, I'd rather people felt the things that I feel, which is excitement and amazement and curiosity and and the feeling that you're enjoying, the sense that you don't quite know what's going on. We can get very addicted to wanting to know things and wanting to be right. But actually, if we can enjoy not understanding things, then maybe we can enjoy math some more because that process of not understanding something is how it all starts. And indeed your son could possibly name the next number. Now he can't invent the next number, but we do run out of names at some point.

LUKE ALBRECHT: I'm wondering, how is infinity stuff?

EUGENIA CHENG: That's a very interesting question. What is stuff anyway? So I think that stuff is things that we don't quite distinguish from each other. And so I would say that you lovely people in this room, you're not stuff, you're people and the chairs aren't stuff because they're all lined up neatly into rows and columns and things. But the things I have at home in my apartment, that kind of stuff, because there's lots of it's not very organized. So the stuff that is all the stuff my my possessions that are organized, I might not think of them as stuff. I don't think there are very many of those. But that then there's this just stuff that we can't quite distinguish. And you might think that infinity is a load of stuff because it's a vast space that is filled with goodness knows what. What is infinite? Maybe is the universe infinite? The maybe there's just air is infinite. So I don't know, then it's not something that you can count or line up. And that's interesting to me because the first kind of infinity that we mathematicians explore is what happens if you just count and keep going. So we can go one, two, three, four, five, six and so on. And if you keep going through all those numbers, there's an infinite number of them. And so that is an infinity, but it's a very organized infinity. It all lines up nicely one after another, like people who are in a neat, orderly queue, not people who are trying to board an airline who are usually not in a neat, orderly queue. And so then the next kind of thing we can think about is if we include other numbers, if we include the fractions and the irrational numbers, that's the decimal numbers that go on forever without repeating themselves. And we discover that those numbers will not line up in an orderly queue and that if you think you have lined them up in an orderly queue, there will always be one that turns out not to be there. Just like if I think I have organized all my possessions, there'll always be another one that turns out to not be part of it, and I'll never be able to organize them all. And so the numbers that include the irrational numbers, those are called the real numbers. There's actually kind of more of them. And I think of that as stuff because they refuse to line up. And I quite like that about them. I don't like it when people don't line up well for the airplane, but I quite like the idea that these numbers are a bit subversive and that they escape and that you can't keep them contained. I like people who want to be contained in the line, and so that maybe is what stuff is it. So you kind of try and keep it contained and it keeps popping out all over the place.

LUKE ALBRECHT: Tell us about why it's important to think about definitions, but also how are ways that we may want to define infinity so that we can think about it?

EUGENIA CHENG: It can sometimes seem pedantic when you talk about definitions, but how often do you get into an argument with someone about something? And it all comes down to the fact that they're using language differently and that they're not fundamentally disagreeing. And at that point, I think it's really important to understand how we're using language and mathematics. I like to think of it not as a subject, but as a discipline. It's a discipline for thinking clearly, and it's a discipline for trying to be as unambiguous as possible in our answers. Maybe social media is the exact opposite of mathematics because it is, as was the worst possible communication and the most possible misunderstandings arise. And I feel that as a mathematician, oddly enough, I can see very clearly where the misunderstanding is coming from, because I can see what each person is using as their form of justification. And because I can separate out, I try to separate out what the definition is, what the steps are that someone has taken, and separate out that from the feelings that we might have about it. That's a discipline where you separate the logic from the feelings, and it means that I can understand a lot. I feel like I'm very good at understanding why people think things, even if I profoundly and very vehemently disagree with what they're thinking. And I've now forgotten what question you ask me.

LUKE ALBRECHT: I think that I think that you answered it very well, I guess, about this idea of communicating and how do we how do we use definitions to help us do that? How how is it that we then can use that idea of defining to help us understand infinity better?

EUGENIA CHENG: Oh, yeah. So it depends what you want infinity to be. And if you want infinity to be a number, you can make it a number. If you want infinity to be a place, you can make it a place. It makes the world a very strange kind of shape, and that's okay. And the great thing about math is that it doesn't have to obey the laws of the world, which is nice because if you want to escape from the laws of the world, you have several choices. You can commit a crime that's not advisable. You can you can sort of go into a dream world. And math is a dream world in which things can be true in that dream world. And although it's not the real world, dreams and fiction shed light on the real world. And one of my favorite examples of that with infinity is the literature and the fiction that's out there about immortality and that we don't have immortality in life. But the fiction about immortality has taught me about life. And one of my favorite operas is the Acropolis case by Janacek, in which one person is immortal. So everybody else is the same. And I think I talk about this in the book, the idea that you change one thing and you try to leave everything else the same and see what happens and what happens in this opera is that we discover that immortality would be terrible and that actually life, if the meaning life gets its meaning from its finiteness. And so to me, that's an example of where something that isn't actually part of life sheds light on a life and thinking about infinity sheds light on the numbers that are not infinite, actually. And it was the drive to figure out infinity that led mathematicians finally to pin down what numbers really are. Because we use numbers all the time. But what are they actually? And people write probably whole theses about what is the number one, and that's not quite what I'm talking about. But even just logically, it turned out that mathematicians, no one really understood what numbers were. And once they did understand, you know, they were getting by perfectly fine without knowing what numbers were. But then they understood it better and then all sorts of things became possible. Electricity became possible, the Internet became possible. Everything that we see around us uses calculus, actually, which only became possible when they understood infinity, the infinitely big and the infinitely small. And without that, where would we be?

LUKE ALBRECHT: How is telling stories important, both as a teacher and an author?

EUGENIA CHENG: I think it's of utmost importance. We're using aspects of life to understand aspects of mathematics and to show that we do parts of mathematical thinking in our life all all the time. And that if we tell a story, a story is a journey, really. It's a journey from where you are now emotionally to where we want someone to be emotionally. And when we're teaching, that's what we need to do. We need to get people from the place that they're at to the place where we would like them to be. And we have to understand that they are starting from the place that they're starting at. It's we can't just pretend that they're starting somewhere else, wish that they knew something else. We have to take them from the place that they're actually at to the place that we want them to go. And so that is a story. It's a journey. And for me, the best way to do it is, is with feelings, because if you do it just intellectually, then it kind of won't stick because the emotions will still be over there. So we have to do it. I try to lead with the emotions and then the intellectual part will follow. I absolutely do not think that math can explain everything, and I do not think that we should even try to get math to explain everything. For me, it's that that every time we answer a mathematical question, it creates more questions. And from that alone, we know that we will never be able to answer all the questions, just like we will never be able to find all the numbers because there's always another one after we found it. But for me, the aim isn't to explain everything using math and logic. The aim is to find what is the logical part in any given situation and put as much into that logical path as possible. Because the logical path is the easy part. That's the part that works the way it's supposed to. Life is much messier than that and much harder than that. So we'll never be able to explain the rest of it. But if we put as much as possible in the logical thought, we can save our most powerful resources of our brain for doing the part that's difficult, that's outside that once we've sort of just put the easy part into the mathematical part. And for me, the where is most interesting to me is the exact interface between the things we can't explain using logic and the things that we can't quite. And so, for example, when a piece of music makes me cry, I'm fascinated by why it makes me cry. And I will analyze why it does. And I can analyze its chord structure and the chord progressions and the cancer melodies. And I'll get to a certain point and I'll say, Oh, it's that suspension right there that makes me cry. But why does that suspension make me cry? That's what I can't understand. And that is where the beauty of it is to me, just beyond what we can explain. And so I have this image that the logical part of what we understand is that the central sphere of all of our understanding and that the surface area is the interface between what we can and we can't understand, and that that logical core is like our physical core. If we have a strong core, we get more access to the rest of our thinking and as we put more and more things into that logical core, the sphere grows and so the surface area grows and so that interface grows. And because that interface is where beautiful things are, we get more and more access to beautiful things.

[Audience applause]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was EUGENIA CHENG and LUKE ALBRECHT at the Chicago Humanities Spring Festival in 2017. For the full story, head to the show notes for the link to the video of this event as well as more information on EUGENIA CHENG’s book Beyond Infinity: An Expedition to the Outer Limits of Mathematics. This mini episode of Chicago Humanities Tapes was produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal. New episodes drop every other Tuesday, available on all streaming platforms. Head to chicagohumanities.org to learn more and check out all our episodes featuring your favorite speakers and some of their big ideas, and you can also find our live event calendar for tickets if you’re in the Chicagoland area. We’ll be back with full episodes starting back up in two weeks. But in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

EUGENIA CHENG: And so that for me is another application of the intermediate value theorem, which is only been proved once mathematicians understood infinity.

LUKE ALBRECHT: That's a lot to take in.

[Audience laughter]

[Cassette player clicks closed]

SHOW NOTES

Watch the full conversation here.

CW: Accessible math concepts

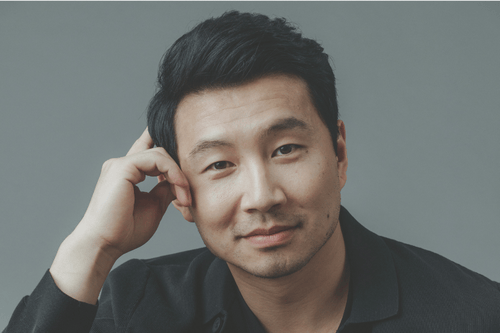

Eugenia Cheng ( L ) and Luke Albrecht ( R ) on stage at the Fine Arts Building at the Chicago Humanities Spring Festival in 2017.

Eugenia Cheng, Beyond Infinity: An Expedition to the Outer Limits of Mathematics

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- April 16, 2024

Mini Tapes: What We Can Learn About Social Media From Foxes

- Podcast

- April 30, 2024

Mini Tapes: Guidance from the Afterlife

- Podcast

- May 2, 2023

Marvel's Simu Liu on Acting, Abercrombie, and Family

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!